The United States Government, acting through the United States Postal Service (USPS) has been ordered to pay US $3.5 million for copyright infringement after accidentally using a replica Statue of Liberty on its 2011 Forever Stamp. The creator of the replica sculpture, Robert S. Davidson, brought a claim against the United States for infringing his copyright over the original and protected work. Mr Davidson has described his work to the media as a sexier version of the original Statue of Liberty. It’s a costly mistake for the USPS which has many wondering how the blunder occurred in the first place.

Background

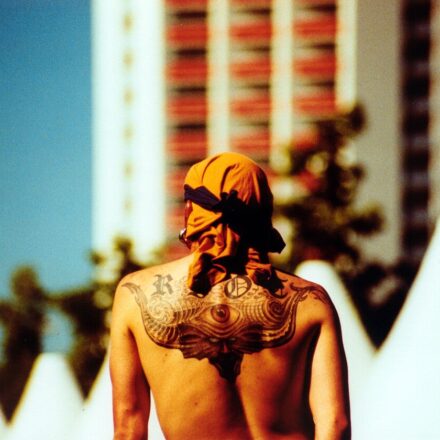

In the mid-1990s Mr Davidson won the tender to create the ‘Lady Liberty’ statue in front of the New York-New York Hotel in Las Vegas. Throughout his passionate testimony, Mr Davidson described his desire to make the final product ‘a little more modern’ and ‘feminine’ than the original, drawing on a photo of his late mother-in-law for inspiration and making facial features softer and more well-defined. Mr Davidson said his replica was more appropriate for Las Vegas.

In 2008, the USPS sought to update the image on its ‘Forever Stamp’ – the workhorse of the US postal system, which remain valid forever, even if the rate of postage rises. The photograph of Mr Davidson’s replica was chosen to feature on the stamp, having been presented to USPS by a contractor as a photo of the original statue. USPS paid $1,500 to Getty Images for a three-year nonexclusive licence for the photograph and proceeded with production.

In 2011, after distribution had already started, USPS found out that the image on the stamp was Mr Davidson’s work and not an image of the original Statue of Liberty as first thought. Nevertheless, with billions already printed at a significant cost, the USPS decided to continue distributing the Lady Liberty stamp without revision.

After his wife saw the stamp at her local post office, Mr Davidson filed an application for copyright registration. Once his copyright was issued in 2013, he brought proceedings against the government for infringing his copyright over his original and protected work. In its defence, the government sought to rely on non-originality, fair use, and a statutory exemption for pictorial representations of architecture.

Decision

In its judgment, the Court focused on three issues:

- whether Mr Davidson’s replica statue can be considered ‘original’ such that it can be the subject of copyright;

- whether a defence of ‘fair use’ applies; and

- how the damages, if any, should be calculated.

There was no dispute about whether the defendant used an image of the replica statue without permission. Despite holding a licence for the photograph itself, the Court held that USPS had no rights to the substance of the image.

Can a replica be ‘original work’?

The Court emphasised that the fundamental principle of copyright is originality, but that originality requires only a ‘minimal degree of creativity’.[1] This is an ‘extremely low’ standard,[2] which only requires the plaintiff to show the independent creation of some ‘original elements’.[3] It follows, therefore, that a work of art does not need to be entirely original for it to be copyrightable.

In this case, the Court was satisfied that Mr Davidson’s statue was sufficiently different to the original Statue of Liberty and able to be subject to copyright. In particular, they agreed with Mr Davidson’s testimony that the facial features of the replica statue evoked a more ‘feminine appeal’, noting the decision in Eden Toys, Inc. v Florelee Undergarment Co[4] which found that minor changes to an illustration of Paddington Bear were non-trivial, as they gave the bear a ‘different, cleaner look.’

Does the defence of Fair Use apply?

The United States Copyright Act provides that, in certain limited circumstances, copying protected material may be characterised as ‘fair use’ and therefore not amount to an infringement. Generally, fair use will apply in circumstances where the copyrighted material has been used for educational or non-commercial purposes, or for a ‘transformative’ purpose to create something new.

In this case the Court determined that fair use could not be established. In particular, they focused on the fact that the photo on the stamps was of the face of the statue—the most distinctive and original part. In its defence, the government sought to argue that the photo was not used for a commercial purpose (despite being sold as stamps) and caused no harm to Mr Davidson’s business. However, the Court rejected this proposition. USPS printed billions of copies of Mr Davidson’s statue and sold them to the public, collecting over $4 billion in revenue. Notwithstanding that the overall profits were low, and that USPS operates at a loss, Mr Davidson was entitled to some form of damages.

Damages

In determining the sum of damages owed to Mr Davidson, the Court considered a range of expert submissions—including opinions about industry standards for art licenses and royalties calculations, the market conditions at the time of production, and USPS’s standard approaches to both acquiring artwork and licensing its own intellectual property. The Court was then left to craft a remedy that reflects fair market value of a non-exclusive licence in 2010, the time at which the licence agreement should have been negotiated.

The bulk of the argument centred on whether Mr Davidson was entitled to a running royalty over the entire production (upwards of four billion stamps) or only over the stamps that resulted in a profit for USPS. Although the Forever Stamp is redeemable at any date in the future, USPS estimates that a certain portion of stamps sold are subject to ‘breakage or retention’ and represent a pure profit.

Ultimately, the Court accepted that granting Mr Davidson a running royalty over billions of stamps would have made no economic sense in the context of licensing negotiations. Furthermore, Mr Davidson would have been in no position to demand such a royalty if he was approached at the time. As such, Mr Davidson was only entitled to the standard $5,000 non-exclusive licensing fee that USPS generally pays in respect of the whole stamp production.

However, the Court considered that stamps that were retained by the buyer, or were lost or destroyed, should be treated as distinct from the production run as a whole. According to USPS, the breakage and retention rate represented roughly 3.24 percent of stamps sold during the time. When applied to the total revenue collected from the Lady Liberty stamp, this amounted to slightly more than $70 million in profit to USPS. Having determined from expert opinions that an average running royalty was around 5 percent, the Court was prepared to grant Mr Davidson a running royalty over the sales of profit-earning stamps, being US $3.5 million.

Some might say Mr Davidson’s sculpture has received the ultimate stamp of approval.

A copy of the judgment can be found at https://ecf.cofc.uscourts.gov/cgi-bin/show_public_doc?2013cv0942-136-0. Thanks to our winter clerk Rohan McPhee for his assistance with this article.

[1] Davidson v The United States (Fed Cl, No 13-942C, 29 Jun 2018) 17.

[2] Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v Rural Tel. Serv. Co, 499 US 340, 345 (1991).

[3] Davidson v The United States (Fed Cl, No 13-942C, 29 Jun 2018) 17.

[4] 697 F.2d 27, 34-35 (2nd Cir, 1982).