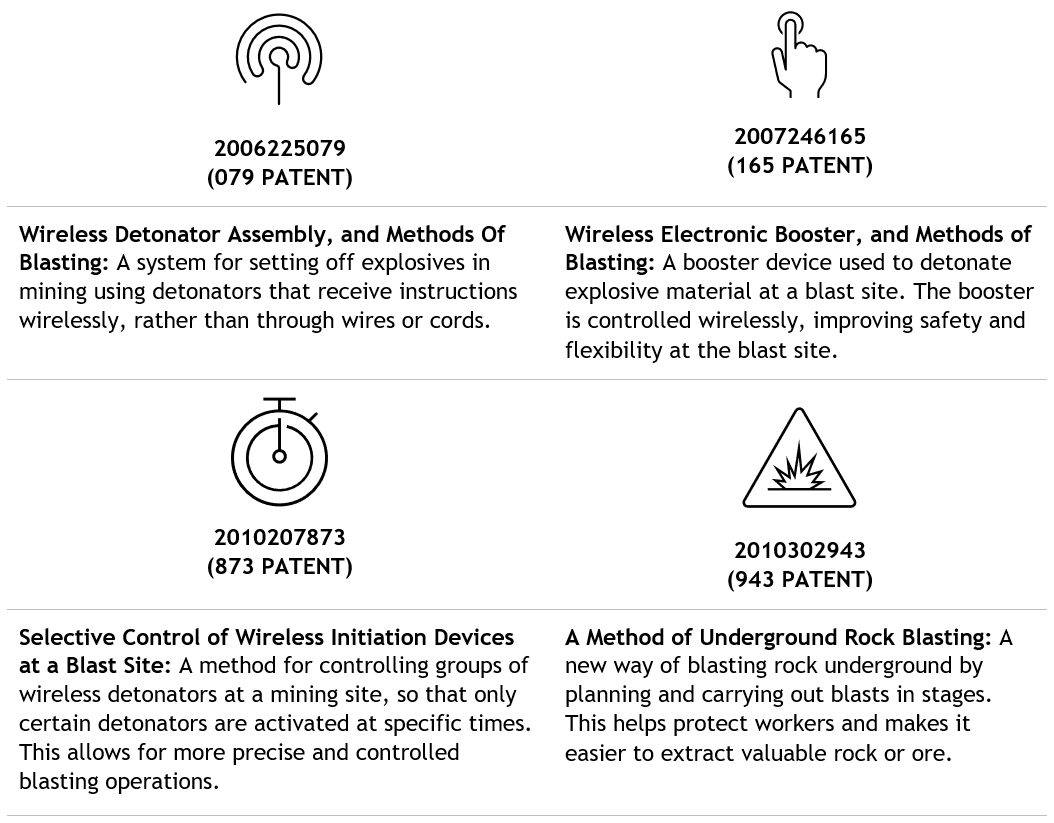

In a long, but intricately reasoned first instance judgment, Australia’s Federal Court has ruled on the validity and infringement of patents relating to wireless detonators.

On 14 July 2025, the Federal Court of Australia delivered a judgment in Dyno Nobel Asia Pacific Pty Ltd v Orica Explosives Technology Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 767. Downes J found that three of four patents asserted by Orica against Dyno Nobel were infringed (the 079, 165, and 943 patents), but not the fourth (the 873 patent). Downes J also rejected all grounds of invalidity raised by Dyno Nobel.

Dyno Nobel’s claim of unjustified threats also failed.

The patents related to a range of technology – wireless detonator assemblies, selective control of detonators, and methods of blasting.

The decision serves as a useful reminder of the importance of selecting appropriately qualified experts in litigation involving multiple patents across related fields and technology, and ensuring that each has the necessary qualifications and experience of the notional person skilled in the art (PSA) – the construct used to assess the validity and infringement of a patent – in each particular field.

Expert evidence

The evidence given by the experts, and their backgrounds and experience, were determinative in this proceeding. Much of the expert evidence put forward by Dyno Nobel was not accepted or given little weight.

In particular, the evidence of Dyno Nobel’s expert witnesses on validity was found not to reflect the perspective of the PSA, including because they were too inventive or too qualified, or because they were infected with knowledge derived from their personal circumstances, in particular, their employment.

Dyno Nobel’s expert evidence was also given limited weight in circumstances where witnesses:

- were found to have misunderstood the concept of common general knowledge (CGK) – in particular, ‘assumed that publication of information is sufficient for the information to be CGK, which assumption is flawed, especially as even he was not aware of it’[1]

- appeared to rely on the affidavits of other Dyno Nobel witnesses, raising doubts about the extent to which opinions were truly their own

- appeared to be acting as an advocate, rather than giving evidence as an independent expert

- were seen to give rehearsed speeches in oral evidence that were not responsive to questions that were asked.

Common general knowledge

As the patents were granted under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) prior to its amendment by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth), the relevant CGK was the information that was generally known to those skilled in the field in Australia at the priority date.

Downes J noted that the kinds of information that form part of the CGK differ between fields, however to be CGK, information must be ‘known to and accepted by all or the bulk of those skilled in the trade’. Here, information resulting from research carried out in a particular role or that was gained through personal experience was not found to be CGK.

Downes J was particularly critical of Dyno Nobel’s submission that the CGK included two wireless detonators:

…the fact that a witness, or even a number of witnesses, had particular knowledge at the priority date does not of itself establish that such knowledge was CGK.

Here, it was critical that wireless electronic detonators (EDs) were found not to form part of the CGK at the priority date – the expert evidence did not establish that those skilled in the art would have known of the existence of these detonators at the priority date.

Novelty

Dyno Nobel alleged that the 079, 165 and 873 patents were invalid for lack of novelty. The Court found that the prior art relied on did not disclose all of the features of the relevant claims, including because the prior art did not disclose the use of wireless EDs.

Downes J found that while the definition of ‘wireless detonator assembly’ referred to ‘a detonator, most preferably an electronic detonator’, the proper construction of the term as understood by a PSA was confined to an assembly which encompasses an ED. This construction was also found to be consistent with the body of the specification which described EDs and provided guidance as to the capacity and function of EDs at the priority date.

Dyno Nobel relied heavily on expert evidence that if a detonator ‘has electronics’, it is an ED. However, Downes J preferred the evidence of Orica’s expert that EDs are to be distinguished from non-electric detonators by features including their ability to program delay times to individual EDs and the ability to receive both analogue and digital signals. These features were key in determining whether the prior art disclosed EDs. In particular, while one prior art document referred to timing delays, the Court accepted Orica’s expert evidence that this was not disclosure of an ED that is capable of receiving a signal (as required by the 079 patent).

In considering whether prior art documents are novelty defeating, Downes J also confirmed that the prior art must be construed as at the date of its publication. This was contrary to Dyno Nobel’s submission that the prior art should be construed at the priority date of the patent in suit.

The Court’s rejection of Dyno Nobel’s novelty arguments was heavily influenced by the expert evidence that was preferred.

Inventive step

Dyno Nobel alleged that all four patents were invalid for lack of inventive step in light of the CGK, either alone or together with specified prior art documents. Downes J again rejected Dyno Nobel’s evidence on inventive step – that is, evidence that the steps leading from the prior art to the claimed invention were routine.

Rather, Downes J accepted Orica’s evidence that the removal of wires from detonators would have been counter-intuitive at the relevant priority dates, including due to prevailing concerns about safety and reliability. It was accepted that the expert evidence demonstrated that the industry trend at the priority date was towards wireless transmission to a receiver connected to the detonator, rather than to a fully wireless detonator assembly.

This illustrates that reliable evidence that a claimed invention was contrary to prevailing trends in the industry at the priority date will be highly persuasive in establishing inventive step.

Other grounds

Challenges to the 079 and 165 patents on the basis of failure to disclose the best method, lack of utility and lack of clarity also failed.

Infringement

Downes J found that the Dyno Nobel’s CyberDet I Device infringed three of the four asserted patents in issue (the 079, 165, and 943 patents). Orica’s allegations of infringement largely succeeded due to findings on the construction of the claims that were premised on Orica’s expert evidence. Downes J criticised the overly technical reading of the claims put forward by Dyno Nobel’s experts, and instead preferred the practical and common sense approach taken by Orica’s experts, finding that such an approach was reflective of the approach which would be taken by a hypothetical non-inventive PSA at the priority date.

Take aways

The Court’s acceptance of the evidence of particular experts highlights the critical role that expert evidence plays in patent litigation, particularly where there are multiple patents in issue across more than one field. The selection of experts who are representative of the hypothetical PSA in each field can be determinative.

[1] Dyno Nobel Asia Pacific Pty Ltd v Orica Explosives Technology Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 767, [103].