Late last year, Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd (Mercato Centrale) officially opened up its Italian food hall ‘Il Mercato Centrale’ on Collins Street, Melbourne. However, visitors to the food hall may be unaware that the proprietors of ‘Il Mercato Centrale’ had been embroiled in a trade mark dispute for the past two years with another Italian-themed retail food business Caporaso Pty Ltd (Caporaso), which had three registered trade marks that included the word ‘mercato’.

Ultimately, the Full Court of the Federal Court Of Australia found in favour of Mercato Centrale,[1] ordering the cancellation of Caporaso’s registration for the plain word mark MERCATO and dismissed Caporaso’s infringement claims against Mercato Centrale.

More importantly for trade mark practitioners, this case demonstrates how important it is not to embellish the degree of use of a trade mark, as failure to do so could render the mark vulnerable to cancellation. It also provides useful reminders on why it is so important to consider trade marks as a whole when registering a trade mark and how it could impact any potential trade mark infringement disputes in the future, as well as how the Federal Court treats non-English words used in trade marks.

What happened here?

Caporaso and its predecessors have owned an Italian-themed supermarket, restaurant and wine retail business in the suburbs of Adelaide since 1972. Initially operating under the names ‘Imma & Mario’s Continental’ or ‘Imma & Mario’s Continental Store’, they later started ‘trading by reference’ to the trade mark MERCATO, registering three trade marks in Australia:

The first two registrations contained an endorsement that ‘The applicant has advised that a translation of the Italian word MERCATO appearing in the trade mark is MARKET.’ The third did not.

They also launched and operated an online food and beverage delivery service at the website address www.mercato.com.au and on related social media accounts from around March 2018.

In 2022, Mercato Centrale announced that they would be opening an Italian-style food hall and marketplace under the name ‘Il Mercato Centrale’ on Collins Street, Melbourne, ‘Centrale’ being Italian for ‘central’.

However, before Mercato Centrale opened their doors in September 2024, Caporaso challenged their use of the word ‘mercato’, claiming that Mercato Centrale had infringed their registered trade marks by using the following unregistered marks that incorporated the word ‘mercato’:

Mercato Centrale denied the infringement claim and cross-claimed seeking orders for:

- the cancellation of the Plain Word Mark and the Fancy Word Mark to the extent they were registered for particular goods and services;

- further and in the alternative, the cancellation of the Plain Word Mark in its entirety or in respect of certain services and

- an order that the registration of the Red Man Logo be rectified by adding a limitation that the registration does not confer any exclusive right to use the word ‘mercato’.

At first instance, the primary judge:[2]

- dismissed Caporaso’s claims of infringement and threatened infringement, holding that none of Mercato Centrale’s marks were deceptively similar to Caporaso’s three registered marks and

- partly upheld Mercato Centrale’s cross-claim, holding that the registration of the Plain Word Mark should be amended to alter the class 43 specification.

Caporaso appealed and Mercato Centrale subsequently cross-appealed the primary judge’s orders to the extent that its cross-claim was dismissed.

Should the primary judge have cancelled the Plain Word Mark?

During the prosecution stages of the Plain Word Mark back in 2016, the Examiner had originally raised an objection under s 41 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (the Act) arguing that the plain word ‘mercato’ was descriptive of its class 35 services (such as retail and wholesale services). In attempting to overcome this objection, Caporaso filed a declaration of use in the name of the managing director, Mr Caporaso, demonstrating use of the Plain Word Mark. The Plain Word Mark was subsequently accepted and proceeded to registration.

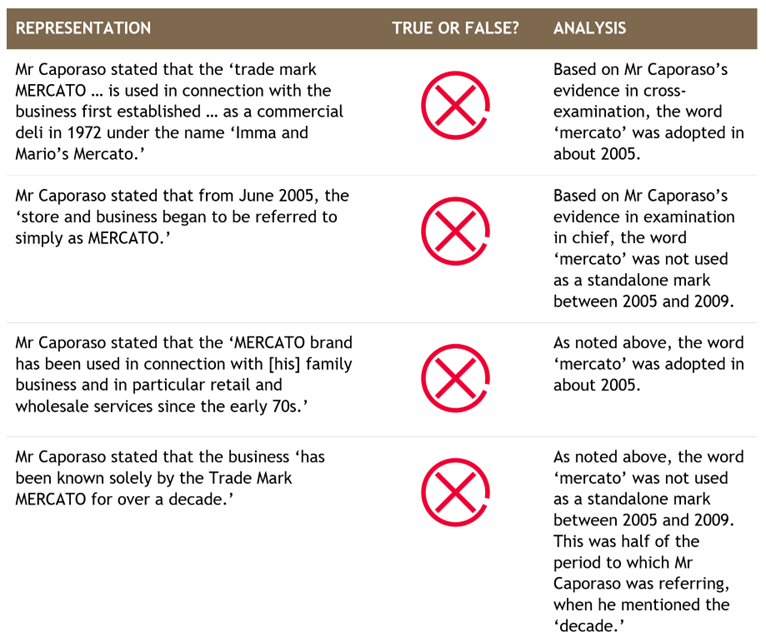

However, over the course of the trial, it came to light that a number of representations made in Mr Caporaso’s declaration were false:

Mercato Centrale sought to rely on these ‘false’ representations as a basis for cancelling the registration of the Plain Word Mark. Mercato Centrale specifically relied on s 62(b) of the Act, which provides a ground for opposing the registration of a trade mark on the basis that the ‘Registrar accepted the application for registration on the basis of evidence or representations that were false in material particulars.’

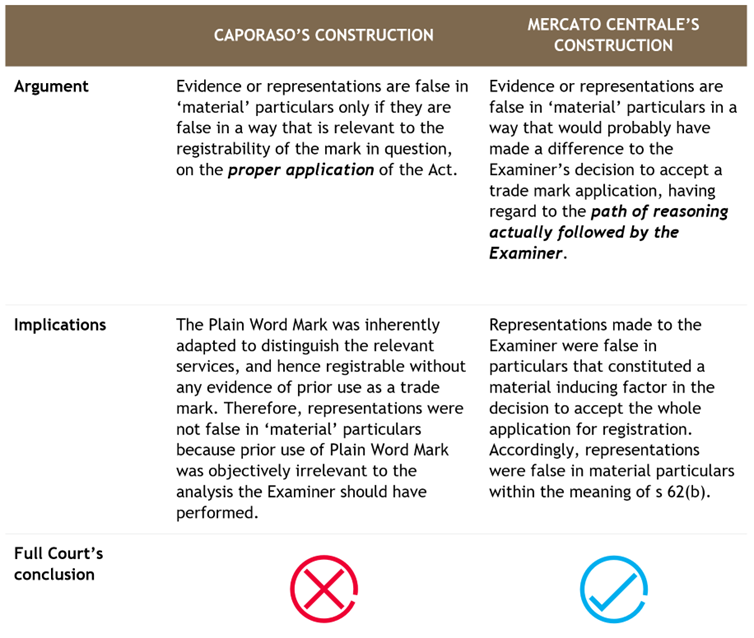

At first instance (which was unchallenged on appeal), it was held that the plain word ‘mercato’ was not directly descriptive of the claimed services, and subsequently the Examiner should not have raised a descriptiveness objection (ie a s 41 objection) in the first place. Given this s 41 conclusion, at appeal, there were competing analyses concerning the proper construction of s 62(b) of the Act.

Ultimately, the Full Court accepted Mercato Centrale’s construction of s 62(b) of the Act and concluded that the ground of opposition under s 62(b) of the Act had been made out in relation to the whole of the registration.

The next question was whether the Full Court should exercise its discretion under s 88(1) of the Act to order the cancellation of the Plain Word Mark. The Full Court looked at the nature and extent of the false representations that secured the acceptance of the Plain Word Mark as well as the public interest in ensuring that the Registrar is able to act on the assurance of trade mark applicants. Taking into account these factors, the Full Court concluded it was appropriate to order the cancellation of the Plain Word Mark.

Should the primary judge have found deceptive similarity between Caporaso’s registered marks and Mercato Centrale’s unregistered marks?

The other key issue at appeal concerned the similarity of Caporaso’s registered marks against Mercato Centrale’s unregistered marks. Were they ‘deceptively similar’ within the meaning of s 120 of the Act?

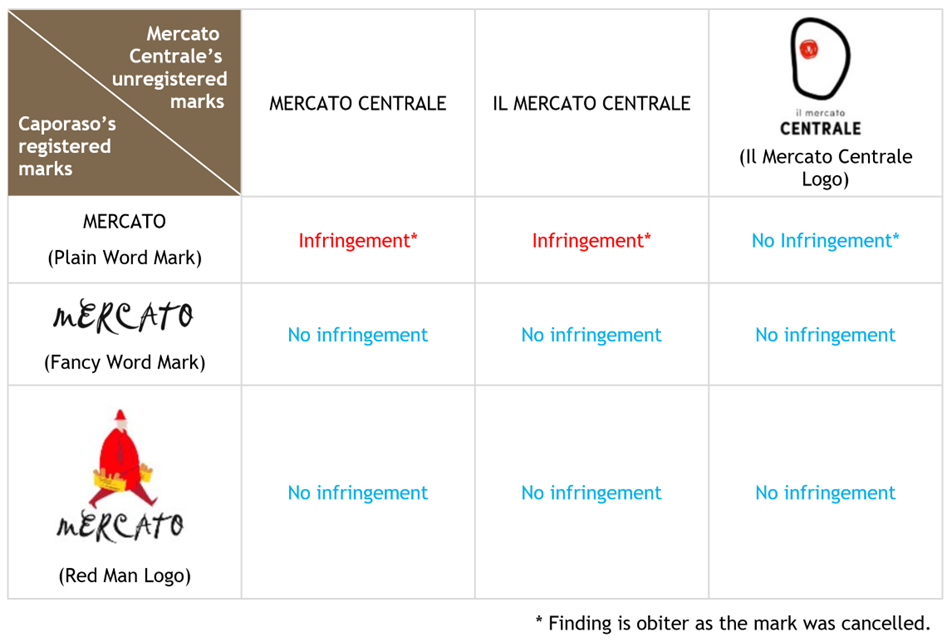

The Full Court methodically compared each of these marks. Below is a table summarising the Full Court’s assessment of deceptive similarity of the relevant marks.

As established above, the Plain Word Mark was cancelled so ultimately the infringement failed in all its permutations. Having said that, the Full Court’s judgment contains useful commentary on the comparison of composite marks, and the significance of additional graphical elements and stylised fonts in the overall assessment of deceptive similarity.

In comparing the Fancy Word Mark with Mercato Centrale’s unregistered marks, the Full Court relevantly stated at [166]-[167] (emphasis added):

‘An essential feature of the Fancy Word Mark is that it is in a fancy script. The monopoly it secures is not a monopoly over the plain word mercato. Rather, it secures a monopoly over that word as rendered in the fancy script depicted on the Register … There is no suggestion that the word mark MERCATO CENTRALE has been rendered in a curly typeface; indeed, as pleaded, it is neutral as to typeface. Consumers would not be caused to wonder, from this use of the mark MERCATO CENTRALE, whether the commercial origin of the MERCATO CENTRALE goods and services is the same traders as stand behind the Fancy Word Mark. A fortiori, neither the word mark IL MERCATO CENTRALE nor the Mercato Centrale Logo infringes the Fancy Word Mark.’

In comparing the Red Man Logo with Mercato Centrale’s unregistered marks, the Full Court stated at [168] (emphasis added):

‘An essential and central feature of the Red Man Logo is the red man it contains. The word marks MERCATO CENTRALE and IL MERCATO CENTRALE have no feature that even approximates the Red Man Logo. The notional consumer, with an imperfect recollection of the registered mark, would not have cause to wonder whether these marks denote the same commercial source as the Red Man Logo. Further, it would take exceptional carelessness or stupidity to look at the Mercato Centrale Logo and wonder whether, because it contains the word mercato and a device with a red dot in its centre, the Mercato Centrale Logo and the Red Man Logo denote the same commercial source.’

The Federal Court’s approach to non-English words

At first instance, Mercato Centrale argued that the word ‘mercato’ had come to be recognised by ordinary Australian consumers, and would be as familiar to English speakers as the words ‘spaghetti’ or ‘cappuccino’ and thus was descriptive. However, the primary judge, applying the leading case of Cantarella Bros v Modena Trading,[3] considered the evidence from Australian dictionaries and experts, and found that the word ‘mercato’ did not bear any ordinary signification in Australia to relevant English-speakers, and therefore their descriptiveness argument failed. This point was not appealed.

The Full Court, however, did consider the consumer understanding of the word ‘centrale’ in ‘Mercato Centrale.’

At first instance the judge reasoned that the two words were to be considered as whole and found that both words are distinctive, both are Italian sounding, and neither word would be readily recognised as a noun or an adjective by an Australian consumer, placing significant weight on the proposition that, in ordinary English, adjectives do not follow nouns. Nor did she think that members of the target audience would consider ‘mercato centrale’ to be a sub-brand of ‘mercato’, as to her mind neither word is less distinctive or more descriptive than the other.

However, the Full Court disagreed, finding that English-speakers could recognise the word ‘centrale’ as meaning ‘central’ and that there are many examples of adjectives that follow nouns, especially for sub-brands, such as ‘Coke Zero, Pepsi Max, Virgin Mobile, Coles Local, MacBook Pro, Samsung Galaxy Ultra, and Nescafé Gold.’ The Full Court found that a substantial number of consumers would look at the mark ‘mercato centrale’ and consider that the word ‘centrale’ is a descriptive addition to that mark, connoting either a variant or sub-brand of MERCATO. Therefore, they would have found infringement if the Plain Word Mark had not been cancelled.

Food for thought

The Full Court’s decision to cancel Caporaso’s registration for the plain word mark MERCATO serves as a valuable reminder that the evidence adduced in the prosecution stages of the trade mark examination process needs to be actively scrutinised and fact-checked to ensure its veracity. It is important that trade mark practitioners do not embellish the degree of use of the subject trade mark, as failure to do so could render the mark vulnerable to cancellation.

This decision also has useful commentary on the comparison of composite marks. The Full Court reminds us that a stylised word mark depicted in fancy script does not confer a monopoly over the plain word itself. Rather, it secures a limited monopoly over that word as rendered in the fancy script depicted on the Register. So, while two composite marks may share a word element, it is important not to ignore the stylised elements of these marks (eg font, colour, and use and placement of device components). This is consistent with the fundamental principle of trade mark law and practice that trade mark practitioners learn from day one, namely, that the comparison of the marks must be assessed as a whole.

Featured image: Daria-Yakovleva, ‘Spaghetti, Tomatoes, Basil image’, Pixabay, 29 December 2016, CC0 1.0 Universal (cropped).

[1] Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 156.

[2] Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 138.

[3] Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd (2013) 299 ALR 752; Modena Trading Pty Ltd v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (2013) 215 FCR 16; Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd (2014) 254 CLR 337.