On 20 May 2024, the Hong Kong Court of First Instance (“CFI”) handed down judgment in SYL v GIF [2024] HKCFI 1324,[1] the first Hong Kong court decision to provide express guidance on the operation of Article 29 of HKIAC’s 2018 Administered Arbitration Rules ( “HKIAC Rules”) dealing with single arbitration under multiple contracts.

The CFI held that GIF, the claimant in the underlying arbitration, was not entitled to commence a single arbitration under multiple contracts as the Arbitration Agreements in question were incompatible. The CFI also found the composition of arbitral tribunal (“Tribunal”) was defective, since it was not done in accordance with the parties’ agreement.

Background

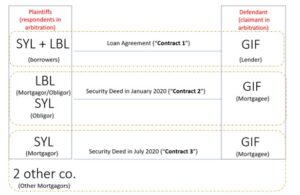

The underlying arbitration involved disputes arising from three contracts. The diagram below sets out the parties to each contract:

Contract 1 contained a dispute resolution clause that provided for Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (“HKIAC”) arbitration with a tribunal of three arbitrators: two wing arbitrators, appointed by each side to the agreement, and a presiding arbitrator, appointed by the parties’ nominated wing arbitrators. Contracts 2 and 3 cross-referenced and incorporated the dispute resolution clause from Contract 1 “mutatis mutandis”. Together, these clauses are the “Arbitration Agreements”.

In reliance on the three contracts, by a Notice of Arbitration (“NOA”) served on 15 October 2021, GIF (the “defendant” in the CFI proceedings) commenced a single arbitration against SYL and LBL (the “plaintiffs” in the CFI proceedings) and the Other Mortgagors, pursuant to Art. 29. The plaintiffs objected to having a single arbitration under multiple contracts. On 10 January 2022, having already decided that the arbitration was prima facie valid, HKIAC indicated that any jurisdictional challenge would be dealt with after the Tribunal was constituted.

SYL and LBL jointly nominated an arbitrator, but Other Mortgagors did not respond to the NOA, nor did they participate in the nomination. For this reason, HKIAC declined to approve the plaintiffs’ designated nominee for arbitrator and instead appointed one itself. The presiding arbitrator was then appointed by the two wing arbitrators, and HKIAC confirmed the Tribunal’s constitution.

SYL and LBL then challenged the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. The Tribunal proceeded to issue an Interim Award on 6 July 2023, which dismissed this jurisdictional challenge. Shortly afterwards, on 11 August 2023, SYL and LBL commenced court proceedings against GIF to have the Interim Award set aside.

CFI Decision

The focus of debate before the CFI was whether the Arbitration Agreements were compatible under Art.29(c). The CFI ultimately agreed with the plaintiffs that the Arbitration Agreements were incompatible with one another, and that the defendant was therefore not entitled to commence a single arbitration under Art.29, which provides:

“Claims arising out of or in connection with more than one contract may be made in a single arbitration, provided that:

(a) a common question of law or fact arises under each arbitration agreement giving rise to the arbitration; and

(b) the rights to relief claimed are in respect of, or arise out of, the same transaction or a series of related transactions; and

(c) the arbitration agreements under which those claims are made are compatible.” (Emphasis added)

Compatibility under Art. 29

The CFI considered the meaning of “compatible” with refence to A Guide to the HKIAC Arbitration Rules and other materials,[2] noting that compatibility relies on there being no insurmountable practical differences between the underlying arbitration agreements. The judge cited several relevant elements which, if not aligned, would render clauses incompatible:[3]

- Preconditions to the commencement of arbitration.

- Appointment procedures.

- The governing law of the arbitration agreements.

- The institutional or ad hoc nature of the arbitrations.

- Seat of the arbitrations.

- The number of arbitrators.

- Any required qualifications of the arbitrators.

- Language for the arbitrations.

- The method for determining fees and expenses of the tribunal.

If the contracts are not aligned on any of these aspects, that difference is likely to be fatal to compatibility. Although the CFI also referred to commentary distinguishing between “fundamental” and “secondary” elements, the CFI’s focus was whether single arbitration would infringe party autonomy and contractual rights.

|

IN FOCUS: PRE-CONDITIONS TO ARBITRATION Parties may be interested to know how the court would regard differences in pre-conditions to arbitration. In this regard, at [35] the CFI referred to Arbitration in Singapore (2nd Ed, 2018), where at §7.150 the text states, ” … Clauses will be considered incompatible if the difference relates to a fundamental element of the arbitration agreement: the institutional or ad hoc nature of the arbitration, the seat, the number of arbitrators, or the appointment procedure. If, on the other hand, the difference relates to a secondary element (law applicable to the merits, steps to be taken before the commencement of the procedure, etc.), the clauses will generally be considered compatible.” (Emphasis added). On its face, this raises a question as to whether a difference between pre-conditions might be regarded as a secondary or “surmountable” factor. However, it should be understood that the commentary referred to was in the context of the consolidation procedure at Article 8.1(c) of the SIAC Arbitration Rules. It stands to reason that in the context of consolidation, where the arbitrations have already been validly commenced, it is immaterial whether there was an identity between any pre-conditions – the respective parties are presumed to have fulfilled those preconditions prior to consolidation. However, in the context of a single arbitration under multiple contracts, pre-conditions to arbitration are a fundamental aspect of the parties’ agreement and any material difference will be irreconcilable. It could not be suggested, for example, that the single arbitration procedure is available in circumstances where one contract mandates a tiered dispute resolution mechanism and the other contract enables either party to proceed directly to arbitration, i.e., without resort to negotiation or mediation first. To adopt one mechanism over another would inevitably deprive one party or the other of their contractual rights (either to attempt, e.g., negotiation or mediation first, or otherwise to avoid that step). |

Incompatibility of the Arbitration Agreements

Applying these observations, the CFI found that the Arbitration Agreements were incompatible as they provided for inconsistent appointment procedures. Although Contracts 2 and 3 incorporated the dispute resolution clause from Contract 1 mutatis mutandis, due to the different parties to each contract, there was an unavoidable difference in the appointment procedure, namely:

- Under Contract 1 and Contract 2, SYL and LBL would have the right to designate an arbitrator and the Other Mortgagors would have no say (as they were not a party to either); whereas,

- Under Contract 3, SYL and the Other Mortgagors would have the right to designate an arbitrator and LBL would have no say (since they were not a party).

This posed an insurmountable problem. The CFI noted that “it infringes party autonomy to impose on the parties a single arbitration when the underlying Arbitration Agreements adopt different appointment procedures.“[4] Under Contract 1 and Contract 2, SYL and LBL had the right to designate an arbitrator of their own choosing to sit on the tribunal. Without such a right, it could not be said that the Plaintiffs consented to arbitrate. By commencing a single multiple-contract arbitration in reliance on all three contracts, the Defendant deprived the Plaintiffs of their right to designate an arbitrator (i.e., because it became necessary to involve the Other Mortgagors in the process). The CFI reasoned that, in these circumstances, there were concerns as to whether the defendants would enjoy an unfair advantage, thereby undermining the integrity of the arbitration. Accordingly, limb (c) of Art. 29 is not satisfied, and a single arbitration under multiple contracts was not permissible pursuant to Art. 29.

The CFI also considered that the Arbitration Agreements were incompatible on the basis that a single arbitration would:

- deprive SYL and LBL of their contractual rights under the Arbitration Agreements (the right to appoint an arbitrator under Contracts 1 and 2 was not shared with the Other Mortgagors and could not be curtailed by the act of the defendant in commencing a single arbitration); and

- give rise to concerns that the defendant may have enjoyed an unfair advantage in the arbitration (the defendant was able to successfully retain an arbitrator of its choosing, whereas SYL and LBL had been denied an equal opportunity, to which they were entitled, of influencing the composition of the tribunal).

The CFI concluded that the Arbitration Agreements which “…contain[ed] differences as to a fundamental aspect of how the Arbitration should be conducted, [were] not “compatible” within the meaning of Article 29…[5]”

It followed from the CFI’s findings on incompatibility of the Arbitration Agreements that the composition of the Tribunal was inevitably defective, as the appointment procedure used differed from the parties’ agreement.

It followed that the award was set aside.

Practical Implications

Where the compatibility and other requirements are met, a single arbitration under multiple contracts can offer a more expeditious and cost-efficient dispute resolution, avoiding the potential for fragmented arbitrations and/or inconsistent awards in relation to the same transaction. However, in SYL v. GIF, the misapplication of Art. 29 ultimately resulted in protracted court proceedings where GIF, who had commenced the single arbitration, ended up bearing court costs and having the Interim Award in their favour set aside. To progress its claims at this point, GIF will have to commence fresh arbitrations.

The decision serves as a cautionary tale for those would-be claimants intending to invoke Art. 29 to bring a single arbitration under multiple contracts. Careful review of the respective arbitration agreements is called for to ensure that they are compatible within the meaning of Art. 29. Furthermore, parties should consider the factual circumstances of the dispute, to ensure that the other requirements of Art. 29 are also met: (a) that there is a common question of law or fact arising under each agreement, and (b) that the rights to relief are in respect of the same transactions (or series of related transactions).

In terms of compatibility, a claimant should check that the relevant arbitration clauses, if not identical, operate with sufficient similarity such that there are no fundamental differences between them. Failure to do so may open the door for jurisdictional challenges as arose here.

Furthermore, the CFI decision complements the HKIAC guidance to Art. 29 demonstrated in procedural decisions published on the HKIAC Case Digest[6]. An earlier HKIAC procedural decision states that “determinations of compatibility in agreed mechanisms should not depend upon potential subsequent procedural developments in the arbitration but should be assessed based on the way in which the arbitration clause was drafted.” (HKIAC Case Digest CD2023/03/04). This again highlights the need for carefully drafted arbitration clauses in a set of related contracts, as subsequent procedural remedies by parties may not overcome the incompatibility in poorly drafted arbitration clauses.

Reflecting the complex commercial environment, provisions allowing a single arbitration based on multiple contracts are now commonly found in institutional arbitral rules. As is clear from this case, making appropriate use of such provisions requires comprehensive case analysis, an understanding of the practical application of the respective arbitration agreements, and knowledge of the respective arbitral institution’s rules, as well as well drafted arbitration clauses.

[1] [2024] HKCFI 1324

[2] At [35] A Guide to the HKIAC Arbitration Rules, 2nd Ed, at §10.125 and §10.126; Arbitration Rules of the Singapore International Arbitration Centre, at Art. 8.1(c)

[3] At [35]

[4] At [38]

[5] At [47].

[6] HKIAC Case Digest is a subscription service providing users with access to certain HKIAC decisions on procedural issues. Complimentary access to case abstracts is freely available. The HKIAC Case Digest platform states that the HKIAC Case Digest summaries are not binding on HKIAC in any way including in any other case.