This post is part of our series on Climate Change Disputes. Our earlier posts include: Climate Change Disputes 101: An Introduction, and a post on Climate Change Trends in Australia (currently, the second most popular jurisdiction for Climate Change Disputes). Stay tuned for future posts on Hong Kong SAR and Singapore.

1. Introduction

China has made domestic and international commitments to combat climate change. China is a party to the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and a signatory to the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change. In September 2020, at the general debate of the 75th Session of the United Nations General Assembly, President Xi Jinping announced that China would scale up its nationally determined contributions, which are at the heart of the Paris Agreement, and that China aims to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. In its 14th 5-year plan, China intensified its commitments and set binding targets to cut carbon emissions per unit of GDP by 18% and to reduce energy consumption per unit of GDP by 13.5% from 2020-2025.

To achieve these goals, a system to enforce climate change policies and legislation is developing. Recent developments in law, policy, and judicial practice are creating the legal framework for climate change disputes in China. As with other jurisdictions, climate change disputes in China will bear unique characteristics of the national legal framework in which they arise. This post reviews this framework and trends we identified in the climate change disputes space in China. Our findings may be particularly relevant to businesses operating in or engaging with carbon and energy-intensive industries.

2. China’s legal framework for climate change disputes

Chinese law consists of an array of legislation that provides a basis for bringing claims related to climate change. This includes the PRC Civil Code (2020), which expressly contemplates liability for “environmental pollution” and “ecological damage”, and the Environmental Protection Law (2014), the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Law (2018), and the Regulation on Ozone Depleting Substances (2018), which together lay the broad framework for regulating environmental and ecological protection. There are prerequisites to bringing claims under this legislation, notably that civil plaintiffs must have an interest in the claims and must prove causation and demonstrate damages in a manner that accords with PRC judicial practice. Consequently, China has created its own public interest litigation (PIL) system that alleviates some of these hurdles and creates a pathway for climate change disputes.

Environmental PILs

China’s PIL system allows public prosecutors and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to bring environmental PILs in civil proceedings against companies and individuals for conduct that harms or creates a material risk of harm to the public interest by damaging the environment or the ecological system. Prosecutors also have standing to bring environmental PILs in administrative proceedings against government agencies for violating their supervisory obligations in matters concerning the environment and the ecology.[1]

Burden of proof and remedies

The burden of proof for an environmental PIL plaintiff in civil proceedings is lower than that for plaintiffs in other types of civil proceedings. In civil environmental PILs, the plaintiff does not need to prove that a defendant acted with fault or intent; it only needs to prove that harm has been caused or would be caused by an act of environmental pollution or ecological damage. On causation, the plaintiff needs to prove “relevance” between the defendant’s conduct and the harm; the burden then shifts to the defendant to prove the absence of causation. In addition, the defendant must provide information about its emission activities if requested by the plaintiff. If the defendant refuses, a court may draw adverse inferences about those activities.

An environmental PIL defendant in civil proceedings may be liable for harm caused to the public interest and may be ordered to stop the polluting or harmful act, eliminate the hazard, restore the environment or the ecology to its original state, pay compensation, and/or issue an apology. Punitive damages are also now available. A plaintiff seeking punitive damages is subject to a higher burden of proof and must prove illegal activity and intent.

In administrative environmental PILs commenced against a government agency, prosecutors must prove that the defendant violated its supervisory duties in matters concerning the environment or the ecology and that those violations harmed the public interest. Proof of causation and damages is not required. Common relief in these proceedings includes invaliding an administrative act and/or directing the defendant to perform its supervisory duties.[2]

Increasing use of environmental PILs

The number of environmental PILs is increasing, particularly after the Environmental Protection Law (2014) and the Civil Procedure Law (2017) clarified the framework for these cases.

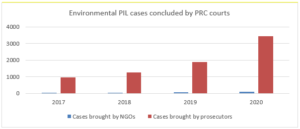

From 2017 to 2020, the number of environmental PILs heard and concluded by PRC courts increased more than threefold, from 1013 cases in 2017 to 3557 cases in 2020. The majority of these cases were commenced by prosecutors, with less than 3% commenced by NGOs. The majority of environmental PILs are civil cases, and many involve parallel criminal and administrative proceedings.

Source: PRC Supreme People’s Court, Environment and Resources Adjudication in China (2017&2018, 2019, 2020)

Emergence of climate change PILs

Despite the number of environmental PILs, climate change cases are only emerging in China.

The PRC Supreme People’s Court (SPC) defines “climate change cases” as those “concerning greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions, ozone depleting substances and other direct or indirect contributors to climate change, including the mitigation cases and adaptation cases”. Only a handful of climate-related cases in China have been reported. We discuss the two widely-reported cases that have been characterized as climate change cases.

In the first case, in 2020, prosecutors in Eastern China commenced an environmental PIL against a local steel company, accusing it of unlawfully releasing ozone-depleting substances over a two-year period. The court concluded that the substances would damage the ozone layer and would thus affect human health and cause environmental and ecological damage. The court ordered the company to pay RMB 746,421 for ecological damage and RMB 150,000 for the cost of assessing damages. In separate proceedings, the same company was subject to administrative and criminal liability, including monetary fines and disgorgement of more than RMB 1.4 million in illegal profits, and its legal representative was sentenced to 10 months in prison.

In the second case, in 2016, an NGO commenced an environmental PIL against a power company in Western China, accusing the company of violating its obligation under the PRC Renewable Energy Law to purchase wind and solar power in the region. The NGO alleged that the company increased air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions by relying on coal power and sought an order requiring the company to comply with its renewable energy purchase obligations and pay damages over RMB1 billion.

The local court dismissed the case. The NGO appealed. The provincial high court revoked the local court’s ruling and designated another court to hear the case. The case is ongoing. The case is notable because it reflects PRC courts’ willingness to accept and hear the case. The case has been designated by the SPC as a typical climate change response and mitigation case.

Air pollution PILs

Relatedly, environmental PILs based on air pollution are also emerging. These cases may not directly involve greenhouse gases (currently GHGs are not defined as pollutants under the 2018 Air Pollution and Control Law), but are aligned with climate change objectives and may capture excessive air polluters who are also major carbon emitters.

Air pollution cases still represent a small portion of environmental PILs. This is likely because establishing causation and damages in air pollution cases is more challenging due to difficulties in tracing air pollutants to a specific emitter and quantifying damages when injury may not manifest immediately or directly.

In 2015, an NGO commenced the first air pollution PIL against a glass company in Northern China for illegally discharging air pollutants. The company repeatedly failed to take corrective action to stop its excess emissions (e.g., by installing waste gas treatment facilities), despite repeated orders and fines by local and provincial authorities. The NGO engaged an institution under the Ministry of Environmental Protection to quantify damages resulting from the company’s illegal emissions. The court relied on the institution’s report (which applied a virtual cost method to estimate the cost of treating the pollution) and the defendant’s repeated emissions violations in rendering its decision. It ordered the defendant to pay RMB 21.983 million in damages and RMB 100,000 for the damage assessment report and to publicly apologize. The company’s factory was also closed and its production lines were moved to another location.

Preventative PILs

Recently, PRC courts have signaled support for preventative environmental PILs, where relief is sought to prevent harm from occurring.

In 2017, an NGO commenced an environmental PIL against a company responsible for constructing a hydropower station in Southwestern China, alleging that the project would threaten the habitat of a rare and endangered bird species. The NGO sought an order directing the company to immediately suspend project construction – before harm to the habitat occurred. Because of the attention attracted by the case, the defendant voluntarily suspended project construction after the case was filed.

The local court ruled in favor of the NGO and ordered project construction to be suspended until an updated environmental impact assessment report was prepared. The NGO appealed and sought permanent project suspension. Its appeal was unsuccessful, but the local court’s ruling was upheld. According to public reports, project construction remains suspended and is unlikely to resume.

While not a climate change dispute, this is the first reported preventative PIL in China and provides non-binding precedent for climate change cases. The SPC recently designated the case as an important case promoting the rule of law.

3. Other types of climate change disputes

Climate change disputes in China may also arise in the context of corporate, consumer, and commercial disputes, among others. Like other jurisdictions, challenges in establishing standing, causation, and damages remain obstacles when pursuing these claims.

Corporate law and governance actions

The PRC Company Law (2018, Article 147) imposes a duty of diligence on directors which generally requires directors to exercise reasonable care and act in the best interest of the company. Directors will be expected to identify, disclose, and manage climate-related risks and to ensure compliance with increasingly robust climate-related regulations. Directors will also be expected to ensure the company’s viability and competitiveness in light of evolving climate-related policies and legislation and the energy transition.

Directors may be exposed to liability if they fail to adequately account for climate risks when planning business operations, fail to adequately disclose climate risk, or fail to manage compliance risks related to climate change. An external example of this type of risk is ClientEarth’s recent action against Shell’s board of directors in the UK alleging failure to adequately prepare for the net-zero energy transition.

Shareholders in China may be inspired by actions in other jurisdictions and may consider claims against companies themselves for failure to manage climate-related financial risk (e.g., by seeking to invalidate a board resolution to participate in a carbon-intensive project) or may consider shareholder action through resolutions calling for companies to adopt measures, plans, or strategies to address climate risks.

Greenwashing claims

Companies operating in China may also be at risk of greenwashing claims. We increasingly see claims by businesses in China that their products or services are “green” or “environmentally friendly”, particularly as China transitions to a low carbon society. PRC companies also face increasing disclosure obligations related to climate change. In 2021, the China Securities Regulatory Commission revised disclosure rules for listed companies and now requires disclosure of administrative penalties for environmental violations and encourages voluntary disclosure of carbon emissions reduction measures. In 2021, China’s Central Bank also issued guidelines that require financial institutions to disclose their carbon emissions.

When companies fail to disclose accurate information about their green energy or carbon activities, they may be exposed to greenwashing claims under PRC law, including the PRC Advertising Law (2021, Article 56), the Law on Protection of Consumer Rights and Interests (2013, Article 45), the Anti Unfair Competition Law (2019, Articles 8 and 17), or the Securities Law (2019, Articles 85 and 87), which generally provide a basis for consumers, businesses, investors, or regulators to seek relief for false or misleading marketing or disclosures. Claims for fraud or misrepresentation may also arise under various parts of the PRC Civil Code or the parties’ commercial contracts.

Similarly, disputes may arise in the investment and financing context, where investors and lenders are increasingly investing with climate change motives or mandates and companies fail to make accurate or adequate disclosures of their climate-related activities and risks. The same may occur in the context of supply chain management, where companies are facing multi-faceted pressure to ensure their supply chains are environmentally sustainable and not unwittingly facilitating carbon-intensive activities.

4. Conclusion

In China, the path for climate change disputes is developing. PILs will likely play an important role in climate change disputes, as legislation evolves and PRC courts and prosecutors are increasingly prepared to hear or pursue these cases. One development we are monitoring closely is the potential change to China’s environmental impact assessment (EIA) system. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment recently issued guidelines that incorporate carbon emissions assessments into the EIA. If embodied into Chinese law, this could broaden the scope of potential disputes where government agencies fail to adequately consider carbon emissions when approving new building and infrastructure projects. As a result, new construction projects may face higher environmental assessment requirements and be exposed to more legal risks, which may affect the timeline or feasibility of planned projects.

Creative plaintiffs may also leverage Chinese company, tort, and other laws to pursue relief against carbon and energy-intensive industries and businesses. Globally, we predict more cases against companies and their directors and cases targeting greenwashing and inadequate supply chain due diligence. Though still nascent, our analysis of past cases shows that, irrespective of the legal outcome, climate change cases can significantly impact projects, policies, and commercial operations.

Additional references

[1] See 2021 PRC Civil Procedure Law (Article 58), 2014 Environmental Protection Law (Article 58), and 2017 Administrative Procedure Law (Article 25) for general legislative support for filing environmental PILs.

[2] See 2021 Civil Code (Articles 1229,1230,1232), 2020 SPC Interpretation of Issues concerning Environmental Tort Claims (Articles 6,7), 2020 SPC Interpretation of Issues concerning Civil Environmental PILs (Articles 13,18), and 2022 SPC Interpretation of Punitive Damages in Environmental Tort Claims (Article 4) for general legislative support for the burden of proof and remedies in environmental PILs.