This post is part of our series on Climate Change Disputes around the world. Our inaugural post was a primer on Climate Change Disputes 101 (click here for link). Stay tuned for future posts on jurisdiction specific issues arising out of Climate Change Disputes.

How the rise in climate change disputes is playing out in Australia?

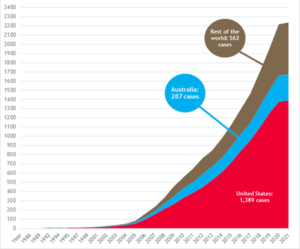

The volume of Climate Change Disputes in Australia is growing. Australia is the second most common jurisdiction, behind the US, in which climate related cases have been brought. At the time of writing, approx. 290 cases have now been brought in Australia, compared to 1390 in the US, and 560 in the rest of the world. Further, the number of cases brought in all jurisdictions is increasing exponentially.

Figure 1 Rise of climate change disputes

The impacts of climate change in Australia are ever more real and inescapable, with devastating bushfires in 2020 and floods in 2022 clearly illustrating the “catastrophic” future that may be in store if things go unchecked. Against this backdrop, the public appetite for legal action on climate change is also increasing.

There are a few key cases that illustrate how the approach to climate change is trending in Australia, and what avenues are being pursued to encourage action.

Greenwashing claims

Greenwashing is a term used to describe the practice of companies selling products, which includes promoting investments, by stating that they have certain “green” credentials when in fact they do not. It can also be used in the context of describing emissions targets which companies set when they do not have a reasonable ability to meet them. Greenwashing in the Australian context is more potent with the unique Australian cause of action of misleading and deceptive conduct arising out the Australian Consumer Law. Under that law, it is illegal for a business to engage in conduct that misleads or deceives or is likely to mislead or deceive consumers or other businesses. This law applies even if there was no intention to mislead or deceive or no one has suffered any loss or damage as a result of the conduct.

Australian Centre for Corporate Responsibility v Santos

The Australian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR), in September 2021, filed claims against Australian oil company Santos. According to its press release, the ACCR alleges Santos’ claims that the natural gas it produces is a “clean fuel” and plans to reach net zero emissions by 2040 are untrue. It argues that Santos’ conduct is contrary to the Australian Consumer Law (misleading and deceptive conduct) and the Corporations Act.

The press release further states that “[Santos’] annual report fails to disclose that the extraction, processing and use of natural gas releases significant quantities of carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere, gases which are key contributors to climate change and global warming.”

This is the first greenwashing case in the world to challenge a company’s net zero emissions target for being misleading (rather than merely inadequate as has been seen in other landmark cases such as the Shell case in the Netherlands).

The case has only recently been filed, but if ACCR is successful, it will set a new precedent which will only add to the pressure on companies to assess and disclose risks, and to report accurately. Given the nature of the relief sought (injunctive to restrain Santos from making future misleading statements) and the activist nature of the claimants, it seems a judgment rather than a settlement is a strong possibility.

Disclosure standards

McVeigh v Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 14

The McVeigh case provides insight into the avenues that activist claimants may pursue to encourage and require investors in major projects (as superfund trustees are) to adhere to higher climate disclosure standards.

In 2018, a 24-year-old industry superfund member sued for an alleged breach by the fund of duties to identify and disclose climate change risks to its investments. The case involved an alleged breach of the statutory duty to provide information to super fund beneficiaries by failing to provide information related to climate change business risks and any plans to address those risks.

The superfund settled, committing to disclose climate risks, and steps taken to address those risks, to members. It also committed to ensuring that investment managers take active steps to consider, measure and manage financial risks posed by climate change and to assess and improve compliance.

While there was no judgment to set precedent, the result was undoubtedly a success for the applicant.

A climate duty of care?

Minister for the Environment v Sharma [2022] FCAFC 35

A landmark decision at first instance

Brought by a group of teenagers from across Australia, the Sharma case addresses the question of whether the federal Minister for the Environment owes Australian children a duty of care when approving the extraction of coal from a coal mine under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act).

The applicants alleged a novel duty of care owed by the Minister to young people in exercising these approval powers. They further asserted that digging up and burning coal will exacerbate climate change and harm young people in the future. They sought a declaration and an injunction before an approval decision was made.

The judge of first instance of the Federal Court of Australia ruled in favour of the teenagers and established a new duty of care to avoid causing personal harm to children. The Court found that the foreseeable harm from the project, if the risks were to come true, would be “catastrophic”, and therefore children should be considered persons who would be “so directly affected” that the Minister ought to consider their interests when making the approval decision.

Final orders were made in July 2021. However, the case has now been appealed by the Minister and a decision has been handed down by the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia.

No duty of care in this case, but the chapter is not yet closed

The Full Court acknowledged the reality of the existential risk of climate change, but found that nonetheless, in this matter, there was nothing the judiciary (at least at the Federal Court level) can do about it – there is no legal duty of care owed by the federal environment Minister to Australian children to mitigate climate risk when considering whether to approve a coal mine expansion.

Chief Justice Allsop and Justice Wheelahan were concerned about the political and policy issues that arise. Chief Justice Allsop saw the court imposing a climate change legal duty of care on the Minister as akin to usurping the role of government: “To the extent that the evidence and the uncontested risks of climate catastrophe call forth a duty of the Minister or the Executive of the Commonwealth, it is a political duty: to the people of Australia.”

Justice Beach disagreed, holding that “policy is no answer to denying the duty”. His Honour rejected the duty in this case but left the door tantalisingly open with this remark: “It is for the High Court, not us, to engineer new seed varieties for sustainable duties of care.”

So, the recent decision, while overturning the high watermark set by the court of first instance, still leaves the door open for future litigants. The three judges reached their conclusions by very different means; this divergence indicates that the obstacle to future success may not be insurmountable.

The applicants in Sharma are now considering whether to seek leave to appeal to the High Court of Australia.

Pabai Pabai & Anor v Commonwealth of Australia

The climate change duty of care may ride again soon. Pabai Pabai & Anor is a pending claim brought in the Federal Court by First Nations’ leaders alleging that the federal government owes a duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable steps to protect them, their traditional way of life, and the marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands from the current and projected impacts of climate change.

The Pabai claim sits on a very different factual matrix to Sharma. It is founded on various international treaties, plans and programs that Australia has entered into specifically concerning the Torres Straight Islands and the Torres Straight Islanders. The plaintiffs in Pabai argue that these treaties, plans and programs give rise to a duty to take action to protect the Torres Straight Islanders in the face of climate change impacts both actual and predicted.

Grounded in these existing obligations and responsibilities of the Australian government, it is in this respect similar to the landmark Urgenda decision against the Dutch government.

What do these trends indicate? Who should take note?

While not always successful, the sheer and increasing volume of climate change disputes in Australia foreshadows what is to come in other jurisdictions.

Australian climate change related disputes are largely spread across administrative law, corporate governance and unique aspects of Australian Consumer Law (namely, misleading and deceptive conduct). Activist litigants are knocking on the doors of the court, seeking to impose a duty to consider and act to mitigate climate change. We are seeing an increasing focus on establishing and enforcing the liability of companies (and their directors) for considering, reporting and acting on the risks of climate change. These cases are being brought on novel and creative grounds, and demonstrate the commitment and persistence of litigants seeking action on climate change.

There is also mounting domestic and international pressure on the Australian government to legislate climate action, which could create a range of new litigation risks.

The guidance of financial regulators has also indicated a shift towards action, with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority releasing guidance on governance, risk management and disclosure of climate-related financial risks. This regulatory shift is representative of the shift in societal expectations.

Climate change disputes have the potential to affect clients across multiple sectors and industries, not merely those directly involved in fossil fuels. As Justice Bromberg noted in Sharma (at first instance) there is a role for the common law to “respond to altering social conditions”, and in the current climate where the appetite for action and enforcing responsibility is on the rise, we can only expect to see more litigation in this area. Further, it is likely we will see more successful litigation as new precedents are set, and arguments refined even on the basis of preceding unsuccessful cases.