Urszula McCormack and Leonie Tear set out the steps to take to manage the case no company wants to encounter: being held to ransom in a cyber attack.

Finding out that customer data has been hacked, exfiltrated and is being held to ransom by an unknown threat actor is a nightmare come true for any company. Unfortunately, it is a nightmare that all companies and financial institutions must plan for as cybercriminals become more sophisticated and more active, with ransomware attacks no longer being an unexpected or unforeseeable event. Indeed, those in regulated sectors are often required to ensure adequate security controls to detect and prevent cyber attacks. Company directors are also under pressure to demonstrate how they are leading their organisations while responsibly managing data, preventing attacks and dealing with them appropriately when they arise.

In this alert we set out the 5 immediate steps to take if held to ransom. We also detail the risks that arise under sanctions, money laundering and terrorist financing laws that any company contemplating making payment in an attempt to secure data must be aware of. We use Hong Kong as a key case study, but similar issues apply in multiple other markets.

In summary:

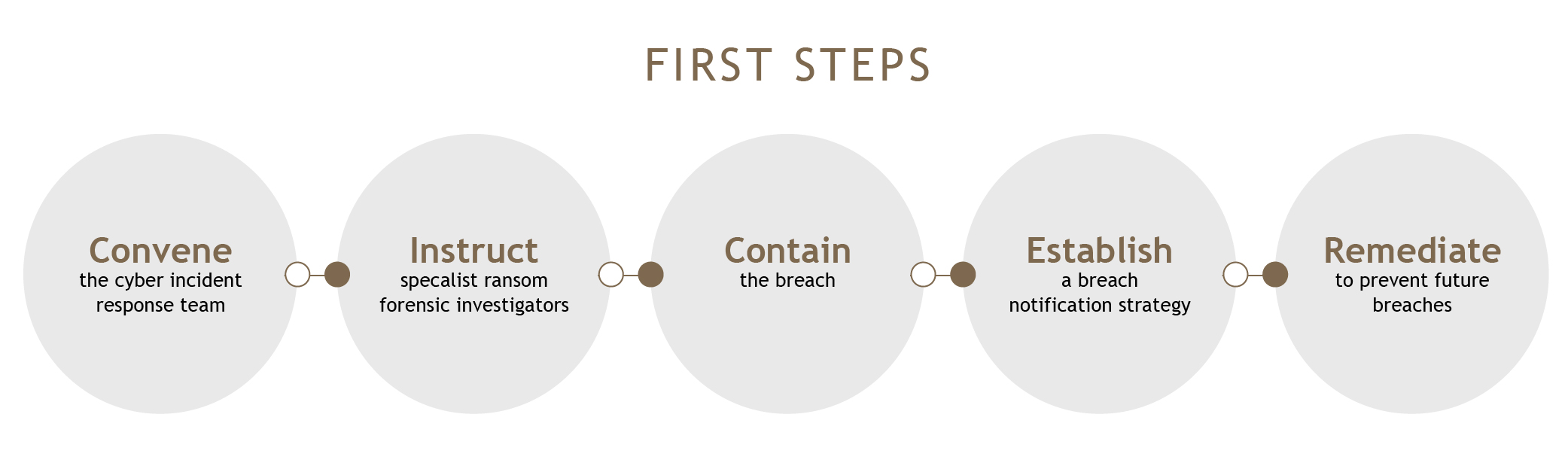

The first 5 steps to take in a ransomware attack

1. Convene a cyber incident response team meeting

With a cyber-attack, speed of response is essential. Having a clear, pre-defined incident response protocol and an established cyber incident response team will save critical hours which will otherwise be used with people in a panic scrambling to react.

The team should be available to convene urgently. If you have a global business, having the team sitting in New York is not going to work when it’s the Hong Kong system that gets hacked. Make sure there are enough people to cover all time zones. Then for any specific investigation, determine:

- the team lead, this should be someone senior and familiar with your IT infrastructure and privacy policies. The person should report directly to the Chief Executive Officer so decisions can be made quickly;

- other representatives. This should include representatives from:

- the legal and compliance team(s);

- the IT team;

- the public relations team; and

- HR, if staff are suspected of any involvement;

- Legal privilege. It is important to consider how investigation materials might be protected under legal privilege. The in-house lawyer may need to direct any investigation. Documents will need to be kept confidential and internal communications kept to a small number of people on a need-to-know basis. Assign a project code name and mark all correspondence accordingly.

2. Instruct ransom forensic investigators

This may be the first time your company has had data hacked, stolen and held to ransom but it happens frequently. Expert companies we work with regularly can help with forensic investigation. These experts can deal with ransom threat actors and you should confirm they have a track record with similar incidents.

The forensic investigators will also be able to assist you with understanding:

- who the likely threat actor is;

- who has been impacted by the breach;

- the volume of the data that has been stolen; and

- what type of data has been stolen and whether it includes identity documents (like passport images), sensitive data, data that could cause humiliation, or financial data that leaves customers vulnerable to fraud attacks etc.

External legal advisors should also be consulted to assist you with understanding notification obligations in relation to both customers and regulators, financial crime risks, risks to individual staff members (eg directors’ liability) and the risks of litigation from impacted customers.

3. Contain the breach

It is essential to identify how the breach occurred and either stop or contain it. This may require the help of specialists who can identify the cause of the issue and recommend what to do to contain the breach. Key steps may include:

- resetting passwords for compromised user accounts and considering whether users should be notified to change the password for other accounts if they use the same one (this may depend on your notification obligations and strategy, considered below);

- disabling network access for computers known to be infected by viruses to prevent it from spreading;

- blocking access for any staff member or user suspected of involvement in the attack;

- if the ransomware strain is known, looking for the right decryption tools online; and

- disconnect backups, most ransomware strains will target backup systems to prevent data recovery.

4. Establish a breach notification strategy

There may be obligations to notify impacted customers either under law or because they need to be alerted to the risk that they may be targeted by hackers using the data that has been taken (ie minimise harm).

There are obligations to notify regulators under the laws of many jurisdictions. Often this will involve a threshold related to “seriousness” or “materiality” that triggers the notification obligation. The obligation may be to notify the regulator within a prescribed timeframe (eg, it is 72 hours under the laws of the European Union (“EU”)). In jurisdictions where there is no mandatory requirement to report a data beach, it may still be sensible to do so. This is particularly if:

- customers need to be notified to ensure they can minimise harm (by changing passwords, alerting their banks etc); or

- the data breach impacts customers in other jurisdictions where notice to regulators is mandatory and the incident is likely to be reported on in the media,

such that it is sensible to inform the relevant regulator directly rather than have them receive the information indirectly. This may impact any enforcement action and penalty issued for failing to protect personal data.

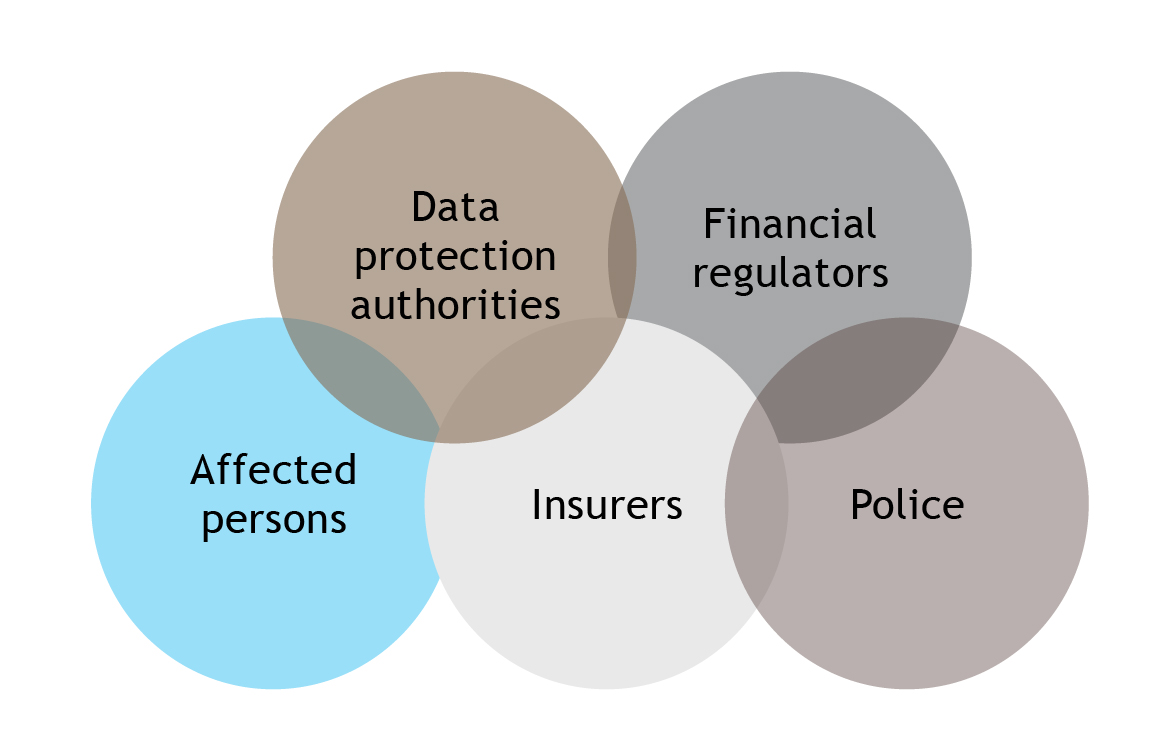

Others may also need to be notified. Common classes of persons who may need (or expect) to be notified include the following:

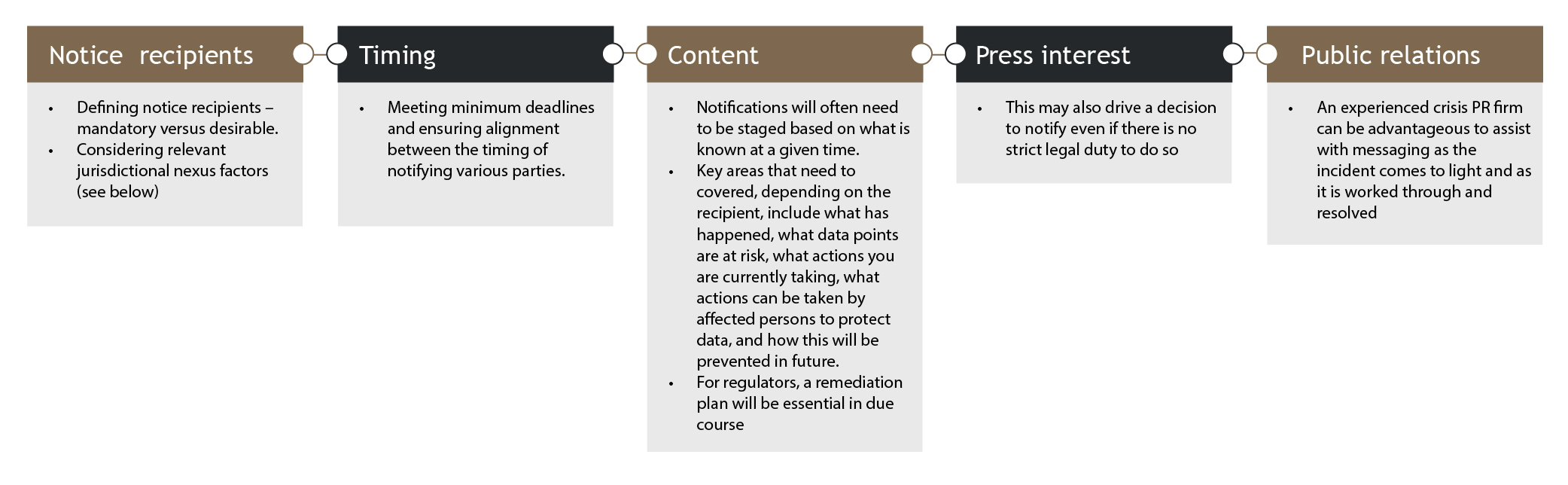

Notifications strategy

A strategy should be formed on who will be notified, when and whether the company will do this directly or through an advisor. Key considerations include:

Contractual obligations

You are likely to have contractual obligations to other parties (including customers) and need to review those contractual obligations. Your contracts may also involve certain representations, warranties, undertakings and liability provisions that relate to data storage and cybersecurity.

You should check for requirements to notify incidents – whether drafted specifically or more generically, confidentiality requirements and provisions relating to storage and cybersecurity – this will also help you size potential contractual exposure from the breach.

A further workstream preparing for legal action may be relevant here, depending on all the circumstances.

Insurance considerations

You should also consider if you need to notify your insurer, your scope of coverage and if your contracts require you to involve your insurer in incident-handling.

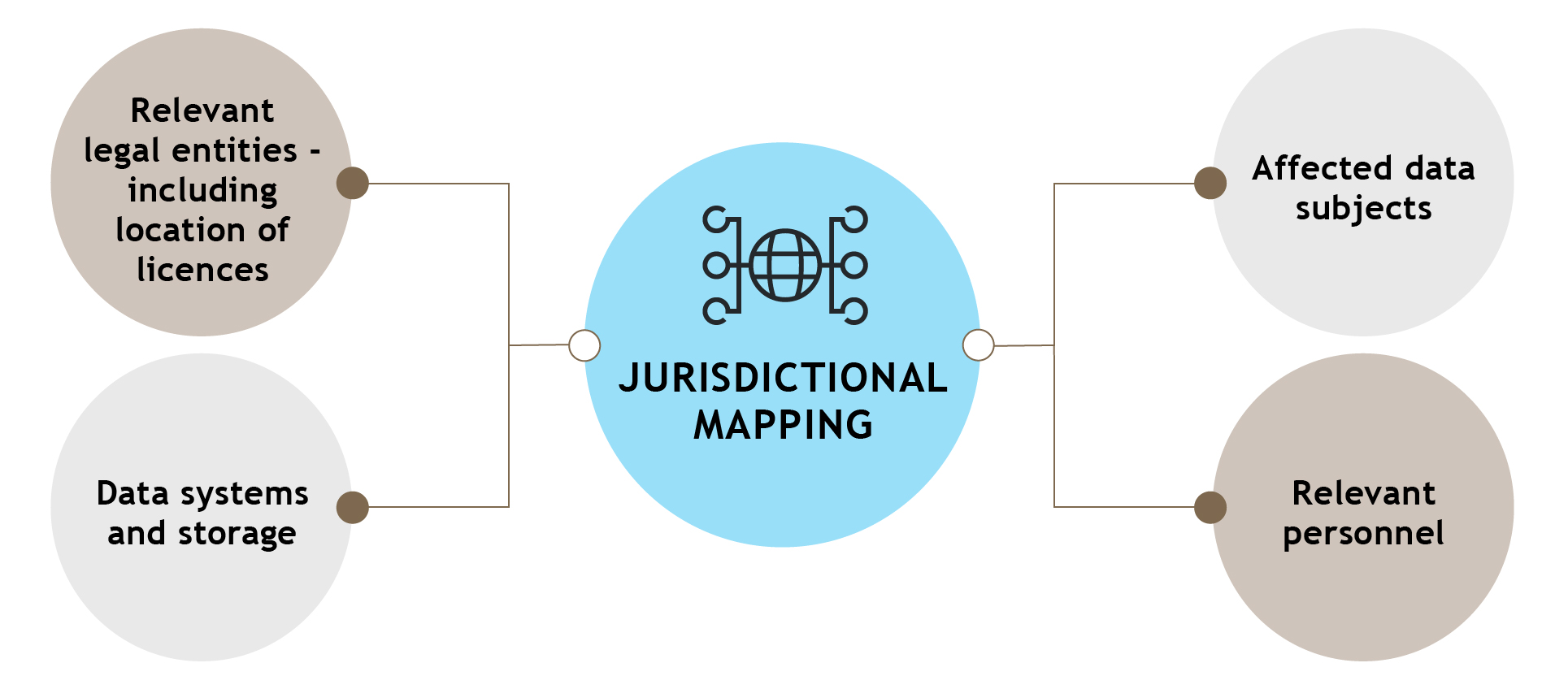

Mapping relevant markets

As noted above, local reporting in relation to the incident itself may also be necessary under local laws. A key step is to map the location of each of the following that is relevant to the cyber incident and data/systems concerned:

Following this, a targeted approach to understanding the reporting strategy in those locations can be taken.

5. Remediate to prevent future breaches

The only thing worse than being hacked and held to ransom, is having it happen again. Any customers that are sympathetic the first time are unlikely to be so kind on round two. Likewise, regulators will take a second violation of any law or requirement far more seriously. To prevent being targeted twice, a thorough review and remediation exercise should be carried out. This will normally require the assistance of a specialist data security consultant who can stress test the current procedures and practices to identify, and patch, weaknesses in the IT systems. Once completed, recommendations should be quickly implemented.

The key legal risks if payment is made – a Hong Kong case study

Paying a ransom threat actor is not, in and of itself, unlawful in Hong Kong. Whilst it may seem immoral and certainly not something any company wants to do, there is no law that directly prohibits payment. This leaves victims in the difficult position of having to balance the harm of payment against the harm of not paying.

The decision is made harder when you do not know who the threat actor is, or their motivation. For example, some hackers say they are working for good, identifying weaknesses in companies’ security systems and alerting them to this, in return for payment. They may not commit any other crimes. Other hackers may well be “criminals”, giving rise to the following key legal risks:

1. Risk of sanctions violations

Many jurisdictions have sanctions programs that specifically seek to target cyber-criminals, this includes under the laws of Australia, the US, the United Kingdom and the EU. Hong Kong does not have such a programme. Sanctions laws can apply on an extraterritorial basis, so it is important to understand which international laws apply in any ransom demand situation.

Sanctions imposed under cybercrime programmes generally impose what is known as an “asset freeze” against the designated persons. One limb of an asset freeze requires that no funds or economic resources are permitted to be made available, directly or indirectly, to, or for the benefit of, the sanctioned person (or their majority owned entities). Alternatively, the ransom threat actor might be in a jurisdiction subject to comprehensive sanctions that prohibit payments to be made to any person within that jurisdiction.

Many sanctions laws impose strict liability, such that an offence is committed if payment is made to a sanctioned person, even if that was not intended. For example, if payment is made to a ransom attacker, and it later transpires the person was designated under applicable sanctions, an offence is committed even if the person paying did not know the identity of the recipient and so could not have known the payment would violate the applicable laws.

Further, if the ransom threat actor is subject to US sanctions, there are additional risks. This is because the US Cyber-Related Sanctions programme carries the threat of secondary sanctions. That is, the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) can sanction any person found to have provided material assistance or financial support to a designated person and paying a ransom could fall within these criteria.

However, to date, those that pay ransoms in response to data hacks have not been targeted by sanctions authorities, including OFAC.

2. Risk of money laundering offences

Payment of the ransom may amount to an offence of money laundering. For example, under the laws of Hong Kong, a person commits an offence if they know or suspect that any property is intended to be used in connection with an indictable offence and they fail to report that suspicion or knowledge to an authorised officer.

Where funds are being paid to a criminal (the cybercriminal carrying out the ransomware attack), there would be grounds to suspect it will be used in connection with a future indictable offence (further cybercrimes).

As such, technically, the payment of a ransom is likely to constitute money laundering under the laws of Hong Kong (and many other jurisdictions, depending on the specific laws).

However, to date, we are not aware of any prosecutions of those that pay ransoms in relation to data hacks. For common law jurisdictions, this may be because the decision to prosecute includes two key considerations:

- there must be sufficient evidence to prosecute the case; and

- it must be evident from the facts of the case, and all the surrounding circumstances, that the prosecution would be in the public interest.

Prosecuting the victim of a crime does not appear to be in the public interest. If a prosecution were brought in a common law jurisdiction, the defence of duress may also be available. This would require a careful assessment of the circumstances.

This landscape may well change as authorities continue to discourage the payment of ransoms. In Hong Kong, the police force has formally joined the anti-ransomware project “No More Ransom” offering an online platform and free of charge services to the public such as analysis of ransomware and decryption tools. The aim is to discourage payment. It is not unlawful to make payment, but as we start to see certain companies refuse to pay ransoms, the public interest may turn to discouraging companies from effectively funding this illicit cyber-attack trade. Looking ahead, we expect there to be a greater demand for clearer legislation and guidance for companies. Our colleagues in Australia, for example, have advocated for this here, for example. In the meantime, this balancing act is essential.

3. Risk of terrorist financing

If the due diligence undertaken by the forensic investigators provides insight into who the threat actor is, it is important to screen terrorist lists. For most jurisdictions, such lists operate under the sanctions regime. For example, the United Nations maintains the ISIL (Da’esh) & Al-Qaida Sanctions List. Certain jurisdictions, including Australia, maintain a separate list of terrorist organisations.

If the threat actor is known to be a terrorist or linked to a terrorist organisation, payment of a ransom would likely be in violation of laws preventing terrorist financing.

However, as with money laundering, prosecuting a victim may not be in the public interest and the defence of duress may be available.

Contact us, anytime

We have a large cross-border team handling data breach and ransom payment issues. Please contact us if we can assist you anytime.