First there were corsets, then shaping underwear (Spanx, anyone?) and now slimming jeans. Often these garments are hidden from view, but the consumer knows exactly what they are looking for leading up to and beyond the point of sale.

But are our decision-makers keeping up with the times when businesses try to protect their valuable brands?

A recent decision in New Zealand represents a backwards step. NYDJ Apparel, Inc’s (second) application to register its “double X” pattern in New Zealand has been rejected based on lack of distinctiveness (NYDJ APPAREL, INC [2014] NZIPOTM 5 (31 January 2014)).

The mark has been registered in Australia (under s41(5) based on a level of acquired distinctiveness) and in various other territories.

Background

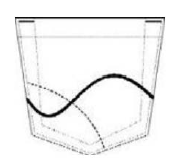

The application was filed on 1 July 2011 in respect of articles of clothing in class 25. A written description of the mark was provided as follows:

The mark consists of a crisscross stitching pattern on the inside pocket of a pair of jeans, as shown in the representation attached to the application. The leg and jeans outline shown in broken lines in the representation forms no part of the mark, but is included to show the location of the mark in use.

An examiner at IPONZ objected to the application on the basis that the mark is a “simple device of two crosses on clothing”. The mark was not sufficiently eye catching, unusual or memorable to act as a brand.

NYDJ argued the point, referring to its mark as a “whimsical design”, and filed evidence of the use of its mark globally, including in New Zealand.

The examiner maintained the objection. The mark was shown on the inside of the goods and so would not be visible to consumers. Consumers would instead see word marks like NYDJ and NOT YOUR DAUGHTERS JEANS as the brands. Further submissions did not work. The examiner considered that due to the “low level of inherent distinctiveness” of the mark, substantial evidence would be required.

This was the second attempt by NYDJ to register its mark in New Zealand. An earlier application filed in 2009 was rejected based on lack of distinctive character.

The matter proceeded to a hearing. NYDJ filed additional evidence from the trade.

The decision

Assistant Commissioner Glover accepted that marks may appear on the inside of products, including clothing. This was more likely to occur with labels and tags, but less common in respect of stitching designs.

The Assistant Commissioner was less receptive to use of the mark in advertising. It was considered that such use was not use on the inside pockets of jeans, and so did not fall within the description of the mark.

As regards third party marks that had been accepted, it was considered that these had a degree of decorative or aesthetic appeal, while NYDJ’s mark was for plain crisscross stitching, which could be seen as having a functional role (strengthening or reinforcing the jeans) or as being a form of very simple decoration.

The applicant’s argument that “simple” marks are memorable and can function to distinguish goods (as is the case with Nike’s Swoosh device) was dismissed. This factor weighed against a finding of inherent distinctiveness.

The acceptance of NYDJ’s mark in Australia and in other countries such as Argentina, Canada, Israel, Japan, Mexico, Panama, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey and the United States was referred to. It was considered that limited weight could be placed on the Australian registration as it was accepted on the basis of evidence of use.

On acquired distinctiveness under s18(2), it was considered that the mark was “at the lower end of the distinctiveness scale”, and as such NYDJ faced a substantial burden under s18(2) in demonstrating that consumers recognize the stitching inside the jeans as a trade mark.

Again, the Assistant Commissioner considered that only use of the mark on the jeans was sufficient. Little of the applicant’s advertising would significantly increase the reputation of the stitching mark. Sales figures were of greater relevance, but it was not clear from the evidence that consumers would see the stitching as a trade mark.

It was also seen that commentators had from time to time formed the incorrect impression that the mark had a functional significance (it did not have such significance, according to the Applicant’s evidence).

On reputation, the mark had been used in New Zealand since 2007. But sales and advertising did not correspond in a linear way to reputation, particularly given that there is very little emphasis placed on the mark in advertising materials. Post-purchase, consumers would not become walking advertisements as the mark would not be visible to others.

There was no evidence of consumer recognition. This would appear to have been particularly relevant in the Assistant Commissioner’s view.

Comment

Aspects of the decision will be troubling for brand owners.

- It is mentioned a number of times (in the examiner’s report, and in the decision itself) that the mark has a low level of distinctive character. Given that s18(1)(b) of New Zealand’s Act only prevents the registration of marks with “no distinctive character”, such a finding should mean that the mark is accepted without more (and without the need to apply s18(2)).

- The ability of several marks to be used at the same time must now be well established. This was recently acknowledged by Wylie J of New Zealand’s High Court in his decision in The Coca-Cola Company v Frucor Soft Drinks Limited [2013] NZHC 3282 (see our note here).

- It appears to be recognized that a mark can acquire distinctiveness even if it appears on the inside of a product. This is in line with the recent decision of Arnold J in Siocété Des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd [2014] EWHC 16 (Ch) (see our note here), in which it was accepted that a mark (in that ca se, the Kit Kat shape mark) may come to indicate the source of goods even if it is not visible at the time of purchase. However, there appears to be little consideration given to the circumstances leading up to the decision to purchase in the context of fashion goods. The relevance of such activities (in the context of an infringement action) was recently discussed in the Jack Wills v House of Fraser decision (see our note here).

Of course, the Assistant Commissioner is not exactly the lone-ranger in taking a dim view of position marks. There have been similar outcomes in various recent EU cases relating to the following marks:

Cases T-433/12 and T-434/12, Steiff v OHIM (“button in ear”)

Case R363/2013-2 Vans, Inc v OHIM

Case T-547/08 X Technology Swiss GmbH v OHIM

Case T-388/09 Rosenruist v OHIM

But there has been an increased acceptance of the branding function played by such signs of this type. A little while back, the 2nd Board of Appeal (Case R-2272/2010-2) accepted Christian Louboutin’s Red Sole CTM (shown below) as being inherently distinctive.

It was considered (and please note that the language is translated from French into English) that the mark “diverges significantly from the standard and the habits of the industry” (paragraph 21), and that the mark is “surprising and unexpected” and “so striking that it will be easily memorable” (paragraph 21). In fact, the many ads for counterfeit products on eBay was also taken as an indication that the red sole functions as a mark.

Even more recently, OHIM’s 2nd Board of Appeal had to consider the registrability of the Shield device mark below (Case R-125/2013-2 Gamp v OHIM).

The 2nd Board held that the Shield device stood out as an independent sign, rather than a piece of functional stitching, which perhaps provides a point of distinction from the NYDJ case. It also made the following comments, providing a breath of fresh air in respect of the necessary analysis:

17 It is common knowledge that devices like the IR holder’s have for many years become increasingly common on clothing and particularly on footwear. The public have become accustomed to identifying a particular brand of running shoe or sports shirt based only on a distinctive pattern or design. The extensive use of advertising on television, Internet and in the printed media have, in the eyes of the relevant public, asserted the power of a design, even a relatively simple one, to be able to act as a distinguishing sign.

18 It is difficult to deny that the IR holder’s mark is not high in distinctive character. It is not abundant in creative effects and it is not particularly original. Nevertheless, for a mark to be registrable, it is not necessary that it be original or fanciful. All it needs to possess to act as a functioning trade mark is a minimum of distinctive character. Nothing more is required.

The reality is that each case will fall to be decided on its particular merits, but perhaps the tide will turn in New Zealand also, such that the starting point is that consumers can instantly recognize such signs as marks.

What about Australia?

As mentioned above, NYDJ’s Australian trade mark application was registered in 2011, having been accepted under section 41(5). That is, it was considered by the AUTMO that the mark had a measure of inherent distinctiveness, and in combination with use/proposed use and any other circumstances, it was convinced that the mark was capable of distinguishing. Christian Louboutin’s Red Sole mark was accepted in Australia under s41(5) also.

Again, given that s 18(1)(b) of New Zealand’s Act only prevents the registration of marks with “no distinctive character”, the decisions are inconsistent with one another. That will not surprise anyone that regularly works in each country.

The lesson here? If you’re going to adopt a position mark, then make sure it’s got that certain something extra.