Caroline Hayward explains the importance of a having a crisis management plan in place and the critical role inhouse counsel will play if a crisis arises.

From our inhouse to yours: KWM’s inhouse-centred series. Written by members of the firm’s Office of General Counsel in Australia, the series gives practical advice to inhouse counsel.

In our latest post, we turn to crises – and, more importantly, how to manage them. Crises can take a number of forms and by their nature they happen unexpectedly without warning. Inhouse counsel have an important role in identifying risks in order to prepare for a crisis. While a crisis is unfolding, inhouse counsel are critical in protecting privilege and providing legal advice in the moment.

What varieties of the beast exist? How to tell you’re in one? And what can you do to respond? Read on.

What is a crisis?

Unfortunately, most of us have experienced one already. A crisis can mean different things to different people. You can imagine that if you catch a cold, it is an annoyance. You might be out of action for a day or two, you might have to cancel that drink with a friend or make sure you don’t run out of tissues. However, if Harry Styles catches a cold – there’s a whole range of issues to consider (especially if the pop sensation has a tour scheduled) and possible knock-on effects.

Inhouse counsel are uniquely positioned to help the organisation determine crises that its business may need to prepare for and manage.

Why do I need to be able to recognise a crisis?

A crisis can cause harm – to an organisation’s people, property, reputation or financial position (in some cases, all of the above). As seen in the recent case of the Titan submersible implosion, sometimes a crisis can be catastrophic.

How do I identify a crisis?

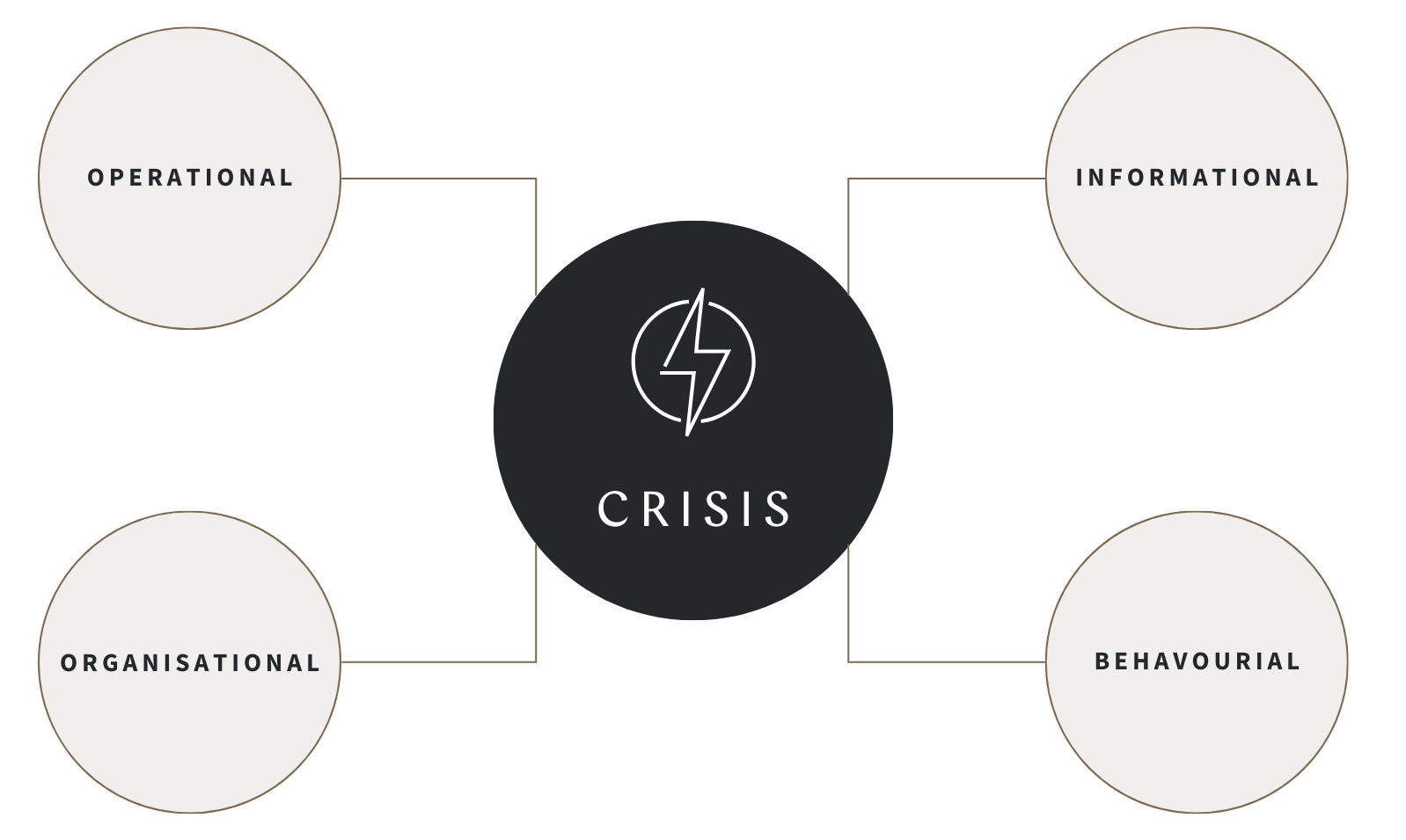

A crisis can be caused by internal or external factors and some risks are inherent to the business. We can roughly categorise a crisis into four general areas.

- Operational: a natural disaster such as a bushfire or flood, volcanic eruptions or a supply chain interruption, which might affect business continuity eg force majeure. This would include the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Technological – virus or cyber threat, something which affects access to the organisation’s system or data. This might cause the organisation’s disaster recovery plan to be put into play. Examples would include the unprecedented global demand on Ticketek’s system for Taylor Swift tickets and the bot attack on Ticketmaster in the US (the scandal is now the subject of a senate enquiry).

- Behavioural: fraud or serious misconduct of a senior executive, something which relates to the organisation’s people and stakeholders (eg Volkswagen emissions scandal aka “dieselgate”).

- Organisational: a takeover bid (eg UBS acquisition of Credit Suisse) or a regulatory investigation, something which threatens the organisation itself.

Now what?

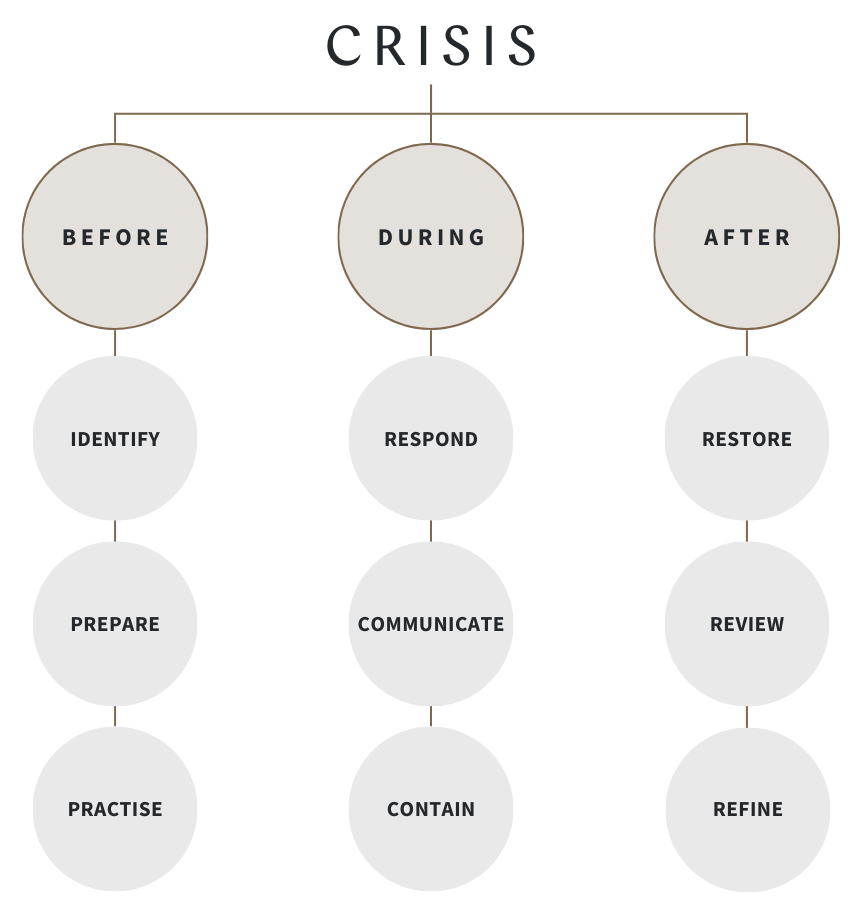

While a crisis can’t always be prevented or mitigated, a crisis management plan (CMP) will help the organisation to navigate it in the moment. Creating an effective CMP requires a skilled crisis management team (CMT).

Who’s on the team?

You are!

Inhouse counsel is a consistent member who will play a valuable role in any crisis – joined by a mix of other representatives.

- Inhouse counsel: A key member of a CMT. Inhouse counsel are uniquely positioned to understand the legal and regulatory requirements of a business, the key risks it faces, remediation options and they provide the benefit of privilege.

- Business representatives: The CMT should also include representatives across all key business functions such as the Chief Information Officer, Chief Financial Officer, Chief Operations Officer, Chief Executive Officer (or their delegate) as well as the people responsible for HR and Communications.

- External parties: You may also have external parties such as cyber experts or specialist lawyers. Not every role will have the same amount of work for every crisis – one might heavily rely on Technology and another crisis might require additional support from HR.

The team should be small and appropriately empowered with a leader who has decision making ability. This leader will not necessarily be the CEO or the Chair – they may be busy elsewhere dealing with other matters or stakeholders or they may not be the right people to front the media or wider public. If the CEO or Chair isn’t directly involved in the CMT, the CMT should understand what level of briefing the CEO/Chair would like so they can appropriately make decisions or have the necessary oversight. The CMT may be empowered to make any decisions necessary or the CEO may want a running briefing to make decisions on certain strategies themselves.

What should the CMP cover?

The key aspects of a CMP:

- Set out roles and responsibilities of the team members with nominated delegates and contact details (including after-hours contact information – a crisis doesn’t care if it’s outside 9am – 5pm)

- The information to enable the team to undertake a risk assessment of the crisis (ie assess the extent of the crisis (minor, moderate or severe), its scope (local, national or global) and the potential damage (insignificant, minor, significant, major or severe).

- The steps required to ensure immediate safety and security of people, premises and assets (including data)

- How to assess impact on supply of goods and services and resource needs

- Draft proactive and reactive internal and external communications to relevant stakeholders (this may include notifying regulators or insurers)

- Have a recovery strategy for usual business operations

An essential part of preparation is conducting a simulation exercise at least once a year on a hypothetical example.

Worst case scenario!

If a crisis takes place, the CMT should assemble and meet (this may be physically or virtually) to implement the CMP. Channels of communication (always have a backup in case usual systems are compromised) and cadence of meeting times (daily or twice daily?) should be determined either in the CMP or, if unforeseen incidents have occurred, at the time.

Inhouse counsel should be prepared to provide legal advice, identify or manage litigation, and reputational risk, review communications and support the CMP.

Communication is key

The communication strategy pursuant to the CMT should be clearly understood. It is considered best to be transparent and honest to give stakeholders comfort and confidence. Template comms for reactive and proactive key messages should be prepared as part of the CMT as it may be necessary to act swiftly and across multiple outlets (eg your website and various social media channels).

An example of poor communication is OceanGate running a job advert for a new submersible pilot while the search for the Titan was ongoing. The company was condemned for the lack of empathy given the worldwide concern for the passengers and when it was hoped they would be found safe.

In certain crises it may be advisable to stay silent and abstain from all usual communications – this will depend on the nature of the crises and whether the external perception is intended to be ‘business as usual’.

For examples, organisations often take a varied approach to keeping stakeholders updated on a data breach – some will provide a steady flow of updates, others will hold off until there is something substantive to report.

Privilege

Inhouse counsel will also need to ensure legal professional privilege is maintained at all times. This can be very difficult in a crisis when they are different people involved at different stages and basically a lot is going on. You should be conscious of privacy obligations when dealing with personal information of individuals and you should maintain the confidentiality of information including restricting disclosure especially in meetings where third parties are present.

Any external providers including those on the CMT should be engaged by inhouse counsel directly and be reminded about the importance of maintaining privileged communications.

For more information about privilege, see our post here for practical tips on preserving legal professional privilege.

Resolution

A crisis can be considered resolved if:

- There’s no longer a risk to people or property (ie the fires have been literally or figuratively put out!)

- Operations are back to normal

- There has been a perpetrator identified (if relevant) and removed

- Media attention and social media activity has settled

- Dedicated time by CMT is no longer required and meetings can be reduced in frequency or ceased.

It’s over!

Not yet! It’s important not to simply walk away once a crisis has been resolved.

Once the team has had some recovery time, a debrief should take place to consider lessons learnt and what modifications may be required to the CMP. As a part of the review, consideration should be given to:

- Whether the CMT and the CMP was effective?

- What went well?

- What were challenges?

- Any need to amend policies or procedures, or refresh education?

- Ensure records are maintained for required period

- Do any people require ongoing support?

- Was resourcing and skill set adequate? Is additional training required?

This then feeds back into pre-crisis planning.

Feeling good?

Hopefully you’ve gained some insights into crises and the value inhouse counsel can bring during each phase, and you feel more confident in the event a crisis arises because you will be prepared and have a plan.

Subscribe to KWM Pulse using the button below so you can stay across recent articles in our inhouse counsel series and other areas of interests.

If your business needs legal advice on crisis management and how to prepare your organisation, please reach out to your KWM contact. Crisis management can be a daunting area as it comes up unexpectedly. If your business needs specialised advice on navigating a technology crisis, please contact Cheng Lim, a Partner in our Telecommunications and Technology team.