This post is part of our series on Climate Change Disputes around the world. Stay tuned for future posts on jurisdiction specific issues arising out of Climate Change Disputes.

What are climate change disputes?

As we have written before, climate change disputes is an umbrella term that encompasses disputes that relate to climate change.

The reference to disputes is broad – it covers litigation, arbitration, complaints made to national, regional and international bodies, and other dispute mechanism procedures. It includes pre-action phases, as well as disputes that settle before creating precedent by way of judgment.

Climate change disputes focus upon climate change law, policy or science as a material issue of law or fact in the case. Typically, such disputes focus upon mitigation or adaptation measures. Mitigation refers to efforts to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions, whereas adaptation refers to adjustments to reduce the adverse impacts of climate change, while taking advantage of potential new opportunities.

Generally, most climate change disputes focus upon catalysing legal, policy and social change on the issue of climate change. However, climate change disputes can also include disputes that focus upon other concerns, yet still have a material impact on global climate change priorities, e.g. actions brought by employees to retain their rights to work in carbon intensive industry (sometimes referred to as ‘just transition’ litigation).

Where are climate change disputes occurring?

Climate change disputes, much like global warming, are a worldwide phenomenon.

It is not uncommon to see a successful action in one jurisdiction influence a string of copycat actions in other jurisdictions, as was seen in the Dutch Urgenda case.

As reported by the Grantham Institute, disputes relating to climate change had been filed before the courts of 39 countries and 13 international or regional courts and tribunals in the year to May 2021.

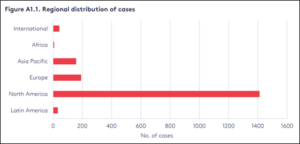

While the vast majority of climate change disputes occur in the USA, Australia is the second most active jurisdiction for climate change litigation, followed by the UK and EU. Disputes are increasingly being identified across Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America.

(Source: J Setzer and C Higham, Global trends in climate change litigation: 2021 snapshot (July 2021) p.42)

How many climate change disputes are there?

The volume of climate change disputes is growing, and has grown exponentially in recent years.

As of May 2021, global databases recorded over 1,800 instances of climate change disputes – of which over a 1,000 were recorded following the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015.

Almost 200 new disputes, being around 11% of all recorded disputes, were filed in the single year up to May 2021, reflecting increased public interest in taking legal action on climate change concerns.

Who are the typical claimants and defendants?

The risk of a climate change dispute is an increasingly serious consideration for the most common defendants: governments and corporations.

This trend correlates closely to those actors that are typically understood to influence global emissions reduction. Government decision-makers agree, issue and enforce climate change policy, whereas the activities of corporations invested in carbon intensive industry have been connected to historical global greenhouse gas emissions.

For example, 63% of global greenhouse gas emissions between 1810-2010 have been attributed to 90 energy and cement companies, dubbed the ‘Carbon Majors’. As at May 2021, there were at least 33 ongoing climate change disputes against the Carbon Majors. Recent examples include Mileudefensie v Shell (which we reported on here) and the more recent action threatened against Shell’s directors for allegedly failing to promote the success of the company by implementing a climate strategy that aligns with the Paris Agreement.

Where climate change disputes appear in the courts, it is commonly in proceedings brought by individuals or NGOs. The Grantham Institute reports that in the USA, NGOs are claimants in almost 60% of cases.

What are the typical causes of action?

The short answer is – there is no typical cause of action.

As we have reported previously, the types of claims and causes of action underlying climate change disputes are diverse. Common causes of action include:

- Constitutional law: these disputes invoke constitutional obligations owed by a State to its citizens. For example, in Neubauer v Germany, the claimants alleged that Germany’s Federal Climate Protection Act violated their constitutional rights.

- Private law: these disputes include causes of action such as negligence, nuisance, trespass or unjust enrichment for damage caused by climate change.

- Consumer protection and fraud: these disputes typically involve alleged misrepresentation, or misleading and deceptive conduct, for inaccurately promoting a company’s “green” investments, products or services (increasingly referred to as “greenwashing”).

- Corporations law: causes of action commonly focus on fiduciary and directors’ duties, including adequate disclosures around climate change business risks in compliance with leading reporting standards, such as the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures.

- Human rights law: the incidence of human rights causes of action continues to rise, reflecting the growing international consensus that climate change threatens a host of human rights, including the emerging right to a healthy environment.

Climate change disputes are marked by their creativity; it is not uncommon to see novel and innovative causes of action being tested in climate change disputes. One example is the novel duty of care that was established in the Australian case of Sharma v Minister for the Environment (which was recently overturned).

What’s next?

Do not expect the topic of climate change disputes to fall off the radar anytime soon. All trends point towards a greater volume, geographical spread, and diversity in the causes of action that underlie climate change disputes, as legal action becomes an increasingly popular tool to pressure governments and corporations to act on the issue of climate change.