We examine the Federal Court decision of AghaeiRad v Plus500AU Pty Ltd (Stay Application) [2025] FCA 1602 (AghaeiRad) and what the decision means for unfair contract terms (UCT) and drafting arbitration clauses in standard form consumer contracts.

On 16 December 2025, in the decision of AghaeiRad, the Federal Court of Australia (Thawley J) held that an arbitration clause preventing Plus500AU’s customers from bringing court proceedings and class actions against Plus500AU was an unfair term and void under section 12BF of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (ASIC Act).

This decision builds on previous unfair contract terms (UCT) cases relating to arbitration clauses, including the decisions of Karpik v Carnival plc (The Ruby Princess) [2021] FCA 1082 (Karpik) and Dialogue Consulting Pty Ltd v Instagram, Inc [2020] FCA 1946 (Dialogue Consulting).

Current state of play for arbitration clauses and the UCT regime

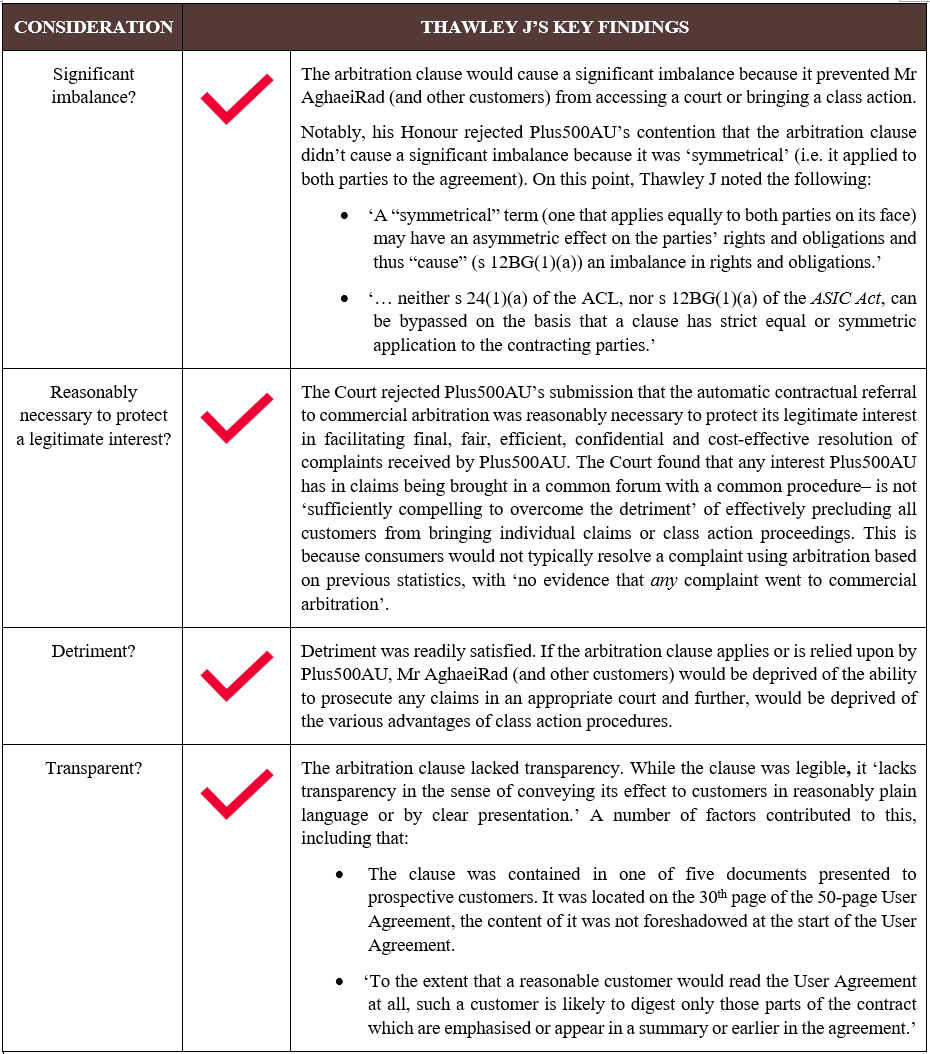

The decision of AghaeiRad confirms that arbitration clauses in standard-form consumer contracts, which have the effect of preventing access to court proceedings or class actions, are likely to be void as unfair. A key insight from AghaeiRad is that the mere fact that a clause applies to both parties will not necessarily lead to a finding that the clause is not unfair under the UCT regime. Ultimately, courts must assess whether the effect of the term is to ‘cause’ significant imbalance and this can still happen even with facial symmetry.

This appears to qualify the Federal Court’s findings in Dialogue Consulting. In Dialogue Consulting, the Court found that Instagram’s arbitration clause requiring disputes to be resolved by arbitration in accordance with the laws of California was not unfair. Key to this conclusion was the Court’s finding that there was no significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and interests as the arbitration clause applied symmetrically to both parties, with each party being able to invoke it. AghaeiRad qualifies Dialogue Consulting’s emphasis on symmetry, tying the analysis back to the statutory focus of the UCT regime on substantive unfairness.

In Karpik, the High Court found a class action waiver clause to be unfair. Both Karpik and AghaeiRad recognise that preventing access to representative proceedings can create a significant imbalance and cause detriment. As such, AghaeiRad applies core principles explained by the court in Karpik in the arbitration context, with the implication that arbitration terms in standard-form consumer contracts that practically deny access to justice may be unfair contract terms.

Further information about AghaeiRad and the key takeaways for businesses with standard form arbitration clauses in their customer contracts is set out below.

Further detail about AghaeiRad

Background

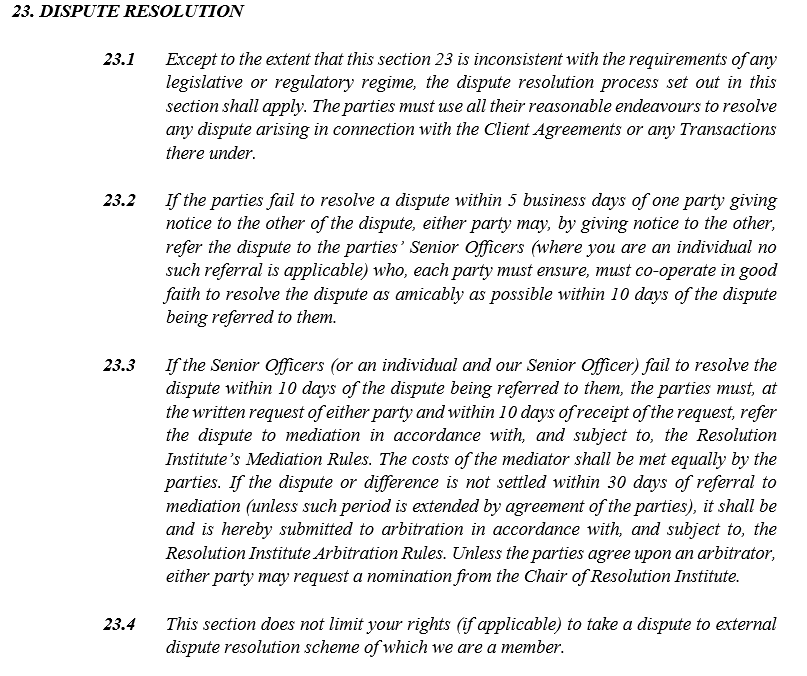

Mr Ali AghaeiRad traded on Plus500AU’s online trading platform for over-the-counter Contracts for Difference (CFDs). After almost a year of trading, Mr AghaeiRad lost the money he had deposited into his trading account and commenced court proceedings against Plus500AU for his loss. Plus500AU sought to rely on a dispute resolution provision, purporting to require the parties to resolve disputes through mediation or arbitration (rather than through the courts). The Federal Court found – among other things – that the dispute resolution provision was void as an unfair contract term under section 12BF of the ASIC Act.

Impugned clause

Court findings

Thawley J concluded that the arbitration term was a UCT voided by section 12BF of the ASIC Act. Below is a summary of his Honour’s key findings.

Drafting tips to manage UCT risk in dispute resolution clauses in standard form contracts

- Clauses which prevent consumers from pursuing individual claims or class actions in court proceedings are likely unfair. The authorities now make clear that class action waivers and mandatory arbitration clauses fall into this category, particularly where the practical effect is to prevent court access/class actions, where arbitration costs are disproportionate to claim values and where the evidence shows that consumers don’t bring claims in that forum. This is the case even if the clause is ‘symmetrical’ (i.e. it applies to both parties on its face).

- Transparency is critical. Terms must clearly and prominently disclose that arbitration excludes court proceedings and representative actions – burying such consequences somewhere in a lengthy clause is likely insufficient. However, transparency alone is unlikely to overcome inherent unfairness.

- Legitimate interests must be substantiated. Pointing to AFSL compliance, or a common forum is inadequate if, in practice, arbitration is rarely or never used to resolve disputes. While each case will turn on its facts, the judgments establish a high bar. In the case of AghaeiRad, the Court found that ‘the real vice’ was that the arbitration term did not provide for the fair resolution of a typical complaint because no consumer would avail themselves of an arbitration (emphasis added). Query whether an arbitration clause could be ‘fair’ if evidence showed that consumers take up complaints in that forum.

- The clause must not go further than reasonably necessary to protect that legitimate interest. Courts are increasingly finding that the availability of an alternative (‘fairer’) option is a factor which is relevant to the UCT assessment. In AghaeiRad, the Court found that interest in disputes being resolved by a common procedure in a common forum could be achieved by other reasonable means, including by an exclusive jurisdiction clause. (And the High Court in Karpik found the exclusive jurisdiction clause in that matter not to be unfair).