It seems apt in the current climatic context that a number of recent Australian trade mark decisions have centred on swimwear and craft beer.

Is my brand even … a brand?

One of the more difficult and nuanced issues in trade mark law is whether a particular sign is being used in a trade mark sense. It’s an often forgotten point, but can often be determinative.

Under Australian law, ‘trade mark use’ is a key threshold issue in demonstrating, among other things:

- That use infringes a registered mark (where the other criteria are met);

- That use supports registration (eg. when pursuing acceptance using evidence-based exceptions such as acquired distinctiveness or honest concurrent use);

- Genuine use of a registered mark (in order to defeat a non-use removal action);

- First use of a substantially identical mark in respect of ‘the same kind of thing’ for the purposes of supporting a claim to ownership.

Unsurprisingly, the overlapping issue of ‘failure to function’ has recently received some high level attention in academic circles in the US.[1]

It is timely then that we have two recent decisions in which the function played by the name at issue – for beers and bikinis – was decisive.

Triangl – DELPHINE functions as a style name for a bikini, but not as a brand

In Pinnacle Runway Pty Ltd v Triangl Limited [2019] FCA 1662 (10 October 2019), Pinnacle brought trade mark infringement proceedings against Triangl for its use of DELPHINE on bikinis. Murphy J held this was not trade mark use because the mark TRIANGL was being used as a badge of origin, while DELPHINE was only used as a ‘style name’.

Murphy J considered the screenshots of the Triangl website, and other advertising materials such as electronic direct mail communications and press releases. Examples of the website screenshots and electronic direct mail communications are pictured below. His Honour considered it unlikely consumers would perceive DELPHINE as the trade source because of TRIANGL’s dominant position on these materials.

TRIANGL appeared in large font on Triangl’s website during the relevant period, at the top and centre of the page. Even in the second screenshot where DELPHINE – FIORE ROSA is a similar font size to TRIANGL, TRIANGL is more likely to be perceived as the trade source because of its position. The inclusion of the colour and print names after DELPHINE (i.e. FIORE ROSA) is also not suggestive of trade mark use. This view was reinforced by other elements such as the domain name which included TRIANGL, being <http://australia.triangl.com>. Murphy J made similar comments in respect of Triangl’s other marketing and promotional materials.

Triangl website screenshots:

Example of electronic direct mail communication:

The context through which consumers would view and arrive at the webpages where the DELPHINE bikinis appeared was also important (citing Shell Co (Aust) Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407). Murphy J stated that it was likely many consumers would navigate to the webpages featuring the DELPHINE bikinis via Triangl’s home page. His Honour inferred that the homepage featured TRIANGL prominently. Murphy J also considered it likely that consumers would scroll through the various bikini styles, each with different style names, when they visited the Triangl’s website. Further, Murphy J accepted Triangl’s evidence which illustrated that consumers were used to seeing women’s names used as style names in women’s fashion (including swimwear).

Murphy J considered that Pinnacle’s ‘central proposition has an air of unreality’. Triangl marketed and sold 35 bikinis with different style names. His Honour considered that the logical conclusion of Pinnacle’s submissions would be that each of the 35 bikini styles would be perceived by consumers as sub-brands of Triangl, with each style name operating as a badge of origin. It was considered more likely that consumers would understand that the style names serve to identify and delineate between the bikini styles, while TRIANGL operates as the trade source. Murphy J observed that many of the names that Pinnacle itself uses as style names for its products are registered by other traders in respect of goods in the same class.

Murphy J also rejected Pinnacle’s contention that DELPHINE is unusual and distinctive to the extent that it is likely to be remembered by consumers and develop its own brand identity. Murphy J did not consider DELPHINE sufficiently unusual or distinctive, and had regard to the evidence adduced by Triangl that suggested consumers typically only remember the head brand and do not recall style names. Murphy J held that DELPHINE was not so unusual or distinctive that consumers would perceive it as a sub-brand. This was reinforced by the finding that consumers were used to seeing women’s names used as a style names for women’s fashion and swimwear at the relevant time.

These considerations led Murphy J to conclude that it was unlikely consumers would perceive DELPHINE as indicating the trade source. They would understand that TRIANGL was the trade source, and would not interpret DELPHINE as a sub-brand of TRIANGL. The use of DELPHINE was therefore not trade mark use and Pinnacle’s infringement claim failed.

Urban Alley – URBAN ALE and URBAN PALE indicate a style or flavour of beer and do not function as brands

In Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirène Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82 (7 February 2020), O’Bryan J considered infringement and validity issues pertaining to URBAN ALE.

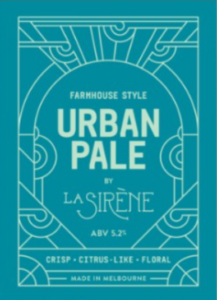

Urban Alley had a registration for URBAN ALE (class 32 beer) with a priority date of 14 June 2016. La Sirène began manufacturing a beer called URBAN PALE in around October 2016, as pictured below. Urban Alley commenced proceedings for trade mark infringement and other claims (passing off, misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law).

O’Bryan J held that La Sirène did not use URBAN PALE as a trade mark, and as such did not infringe.

La Sirène argued that it did not use URBAN PALE as a trade mark because ‘La Sirène’ is clearly the trade source. ‘La Sirène’ is in stylised font and ‘by’ is used in between ‘Urban Pale’ and ‘La Sirène’. La Sirène submitted the use of ‘by’ makes it clear that ‘Farmhouse Style Urban Pale’ is the style of beer, while ‘La Sirène’ is the source.

Urban Alley argued that La Sirène used URBAN PALE as a trade mark for 3 reasons:

- URBAN PALE is the dominant name on the label – it appears in larger lettering than La Sirène, and in a different colour and font. Urban Alley suggest that La Sirène has in fact chosen to use two trade marks on the label, being both LA SIRÈNE and URBAN PALE. One mark is for the product name, one is for the brewer. Urban Alley submitted this was analogous to the branding approach of Carlton & United Breweries for its product ‘Victoria Bitter’.

- La Sirène used URBAN PALE on its own on its website and social media.

- La Sirène filed a trade mark application for URBAN PALE (this was later abandoned).

O’Bryan J held that URBAN PALE was used as a ‘product name’ that described the style and nature of the beer. His Honour acknowledged that URBAN PALE is the most prominent name on the label because of the large, bold font. However, his Honour did not consider that its prominence meant that the otherwise descriptive name was a trade mark for the following reasons:

- First, O’Bryan J considered the words ‘by La Sirène’ still sufficiently prominent on the label to indicate that La Sirène is the trade source. The words clearly convey the message that the product was made by La Sirène.

- Second, O’Bryan J considered URBAN PALE to be ‘overwhelmingly descriptive’. When considering the question of whether Urban Alley’s own mark URBAN ALE should be cancelled, O’Bryan J found that URBAN ALE was not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish. His Honour considered ‘urban’ to be a generic and laudatory term that connotes inner-city craft breweries and craft beer. He considered the evidence about the common use of ‘urban’ in the industry in association with the inner-city craft beer movement. Similarly to URBAN ALE, the term URBAN PALE is descriptive because the words together suggest a craft beer in the style of a pale ale.

- Third, O’Bryan J rejected the contention that La Sirène has often used URBAN PALE on its own on social media and its website. La Sirène’s social media account and website feature the La Sirène brand prominently.

Finally, O’Bryan J placed no weight on the abandoned trade mark application for URBAN PALE. While intention can have a bearing on trade mark use, O’Bryan J emphasised that it is ‘essentially an objective question’. For these reasons, O’Bryan J held that La Sirène did not use URBAN PALE as a trade mark and did not infringe Urban Alley’s trade mark.

Urban Alley was also unsuccessful in its ACL and passing off claims, due to insufficient evidence of its reputation in URBAN ALE. Its application to cancel La Sirène’s marks also failed, but La Sirène succeeded in cancelling the URBAN ALE mark. As indicated above, URBAN ALE was not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish and was deceptively similar to a third party registration for URBAN BREWING COMPANY. La Sirène also cross-claimed under s 129 that Urban Alley made groundless threats to bring legal proceedings against it. This claim failed because the actions in question were by Urban Alley’s predecessor in title.

Watch this space

The Triangl decision has been appealed. The Urban Ale case is still within the appeal period.

These decisions will not be of great surprise to Australian practitioners, given the long history of ‘no trade mark use’ findings in infringement and various other contexts. The decisions serve to highlight the importance of the trade mark use threshold, and provide some helpful guidance in making the relevant assessment based on the specifics of a particular case. The following factors are all likely to be relevant:

- Characterisation of the particular sign or signs at issue, and whether it is used in a standalone or composite sense;

- The nature of the sign, including whether it is descriptive on the one hand or distinctive or unusual on the other:

- The context of the use, including how a consumer encounters it (eg. on a website);

- The practice in the relevant trade;

- Whether the user also applied to register it as a trade mark (albeit this is not conclusive);

- The manner of use including whether it is secondary to an ‘obvious’ house mark (which is not to say that only one brand can be used at a time).

Of course, the dividing line between what is descriptive and distinctive can in itself be murky. Further, as the Urban Ale case shows, the fact that a sign is more prominent than a house mark is not determinative.

If the above leaves you with a thirst for more (sorry), then feel free to read our earlier articles on trade mark use (or not) on t-shirts here, which touches on the related issue of exactly what goods and services the mark is used in respect of.

This article was prepared by Bill Ladas and Madeline Close.

Featured image: Basile Morin, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Alexandra J Roberts, Trademark Failure to Function, 104 Iowa L. Rev. 1977 (2019); Laura A Heymann, What we’ve got here is a failure to indicate (review of Trademark Failure to Function article); Mark P McKenna, Trademark Use Rides Again, 104 Iowa L. Rev. Online 105 (2020):